Yuzuo Tu: An Illustrated Manual of Jade Crafting (玉作图)

Overview

This 12-panel illustrated manual, titled Yuzuo Tu (玉作图), was created by Li Chengyuan (李澄渊), a Qing Dynasty artist, in 1891 at the request of British scholar and sinologist Stephen Bushell (卜士礼). Commissioned to document traditional Chinese jade crafting techniques, it meticulously details 13 core processes—from raw jade extraction (Chuixi 捶析) to final polishing (Pituo 皮碢)—paired with annotated diagrams of tools and workflows. Now preserved in collections like the National Library of China, this manual bridges imperial craftsmanship and cross-cultural exchange, offering unparalleled insights into Qing-era jade artistry.

Structure & Symbolism

Processes and Tools

Each panel combines color illustrations with bilingual annotations (Chinese-Manchu). Key steps include:

- Chuixi (捶析, Pounding and Splitting)

- Tools: Dazhang (大砧, stone anvil), Tiechui (铁锤, iron hammer).

- Process: Raw jade boulders are split using hammers and chisels. The accompanying poem notes: “凡玉初剖,宜施重器” (“Raw jade must first be split with heavy tools”).

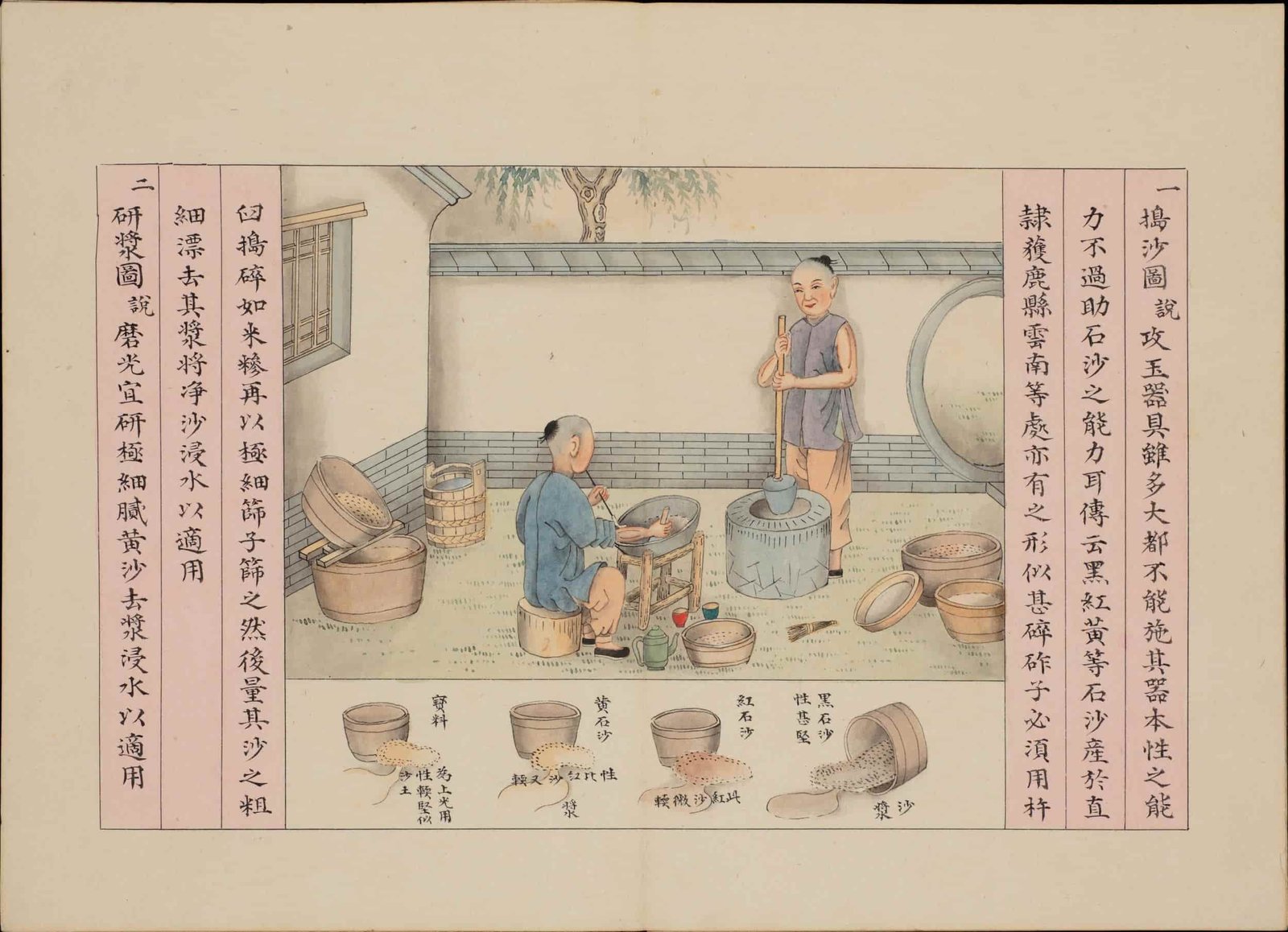

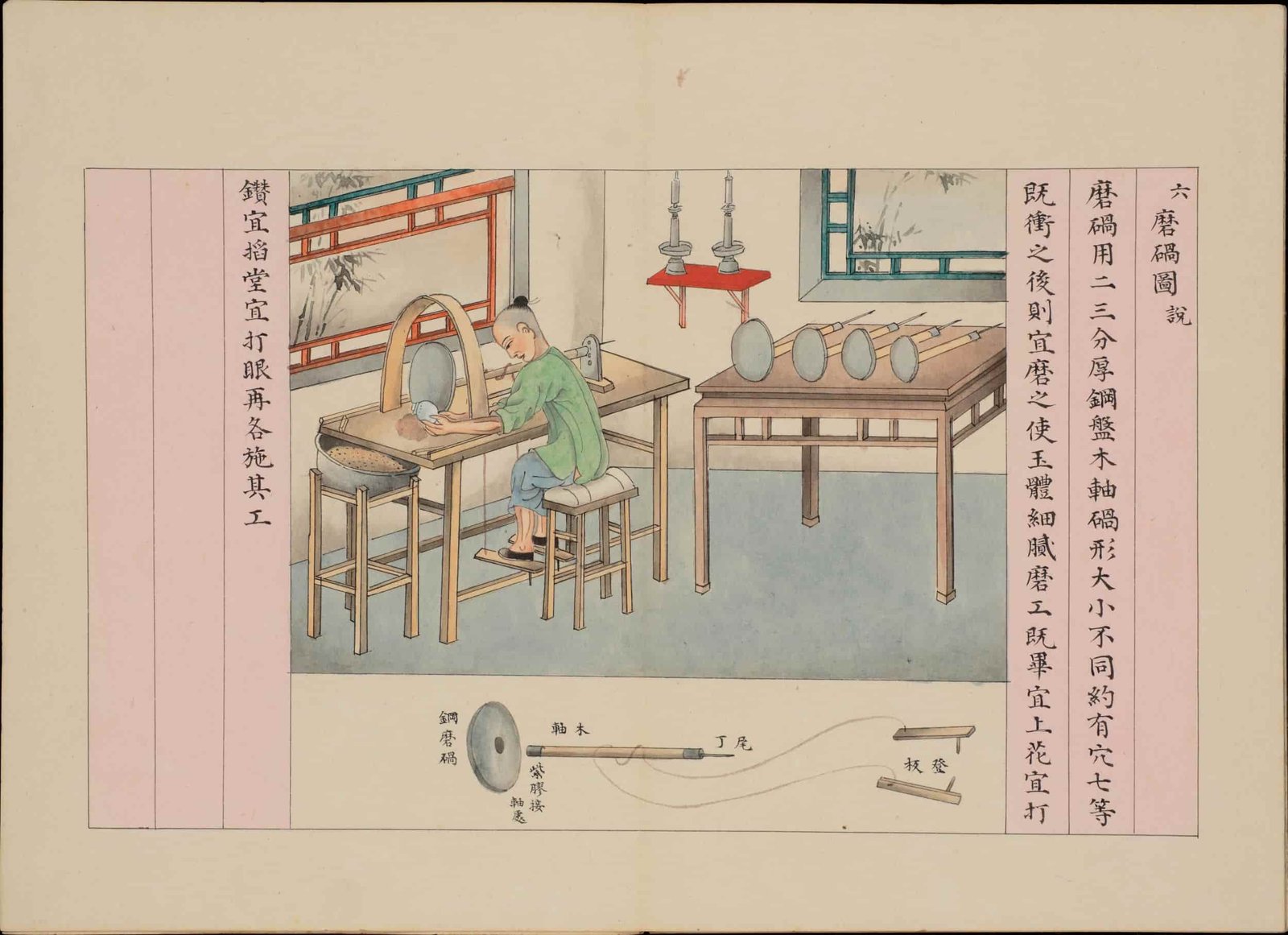

- Yanjing (研浆, Grinding Slurry)

- Tools: Mopan (磨盘, grinding wheel), Heishisha (黑石沙, black quartz sand).

- Symbolism: The slurry’s fineness determines the jade’s luster, reflecting Confucian ideals of refinement through labor.

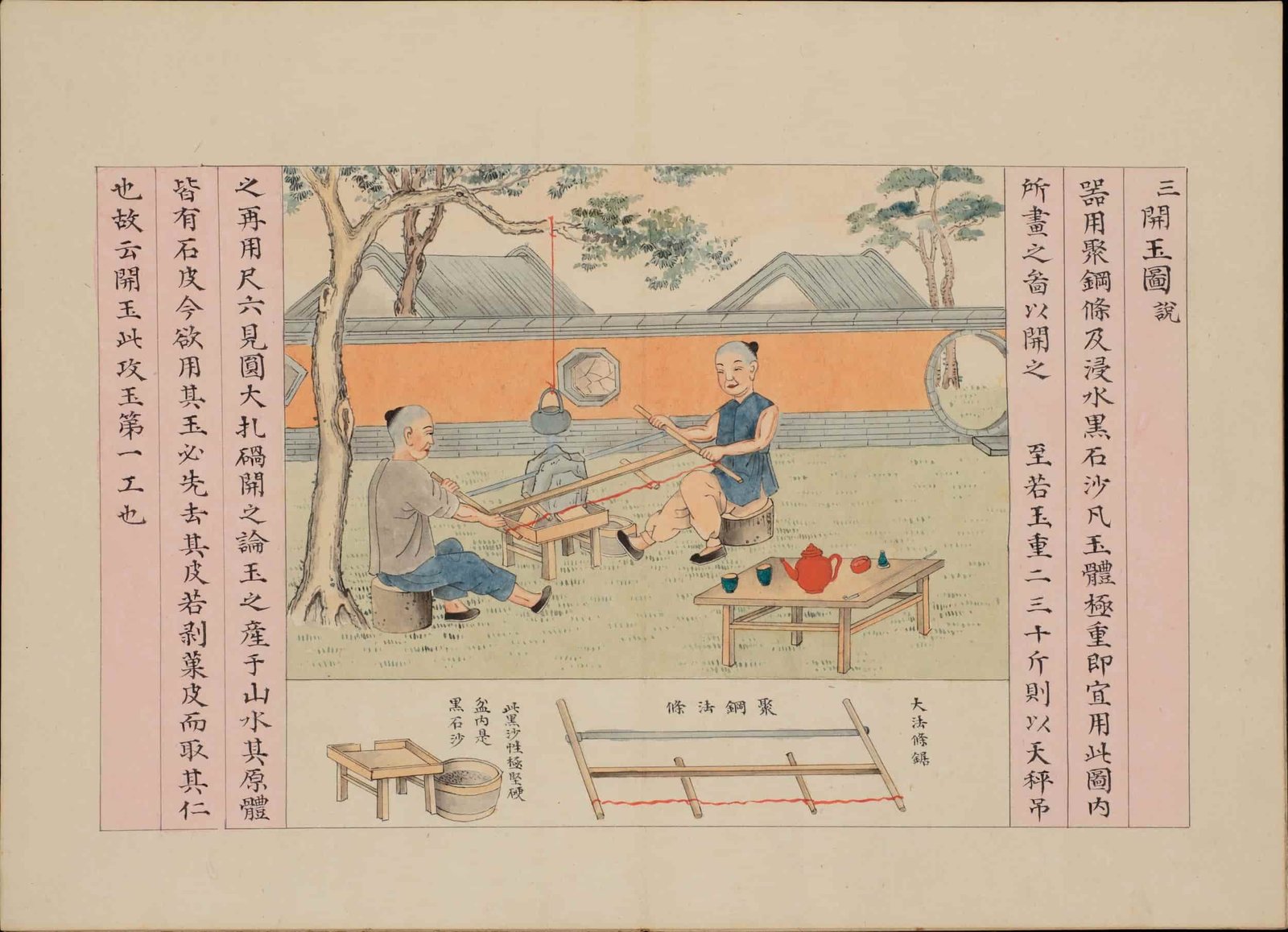

- Kaiyu (开玉, Splitting Jade)

- Tools: Jutiao Ju (聚条锯, steel wire saw), Tianping (天平, counterweight pulley).

- Process: Large jade blocks are cut using sand-coated wire saws—a technique later adopted in Renaissance Europe for marble sculpting.

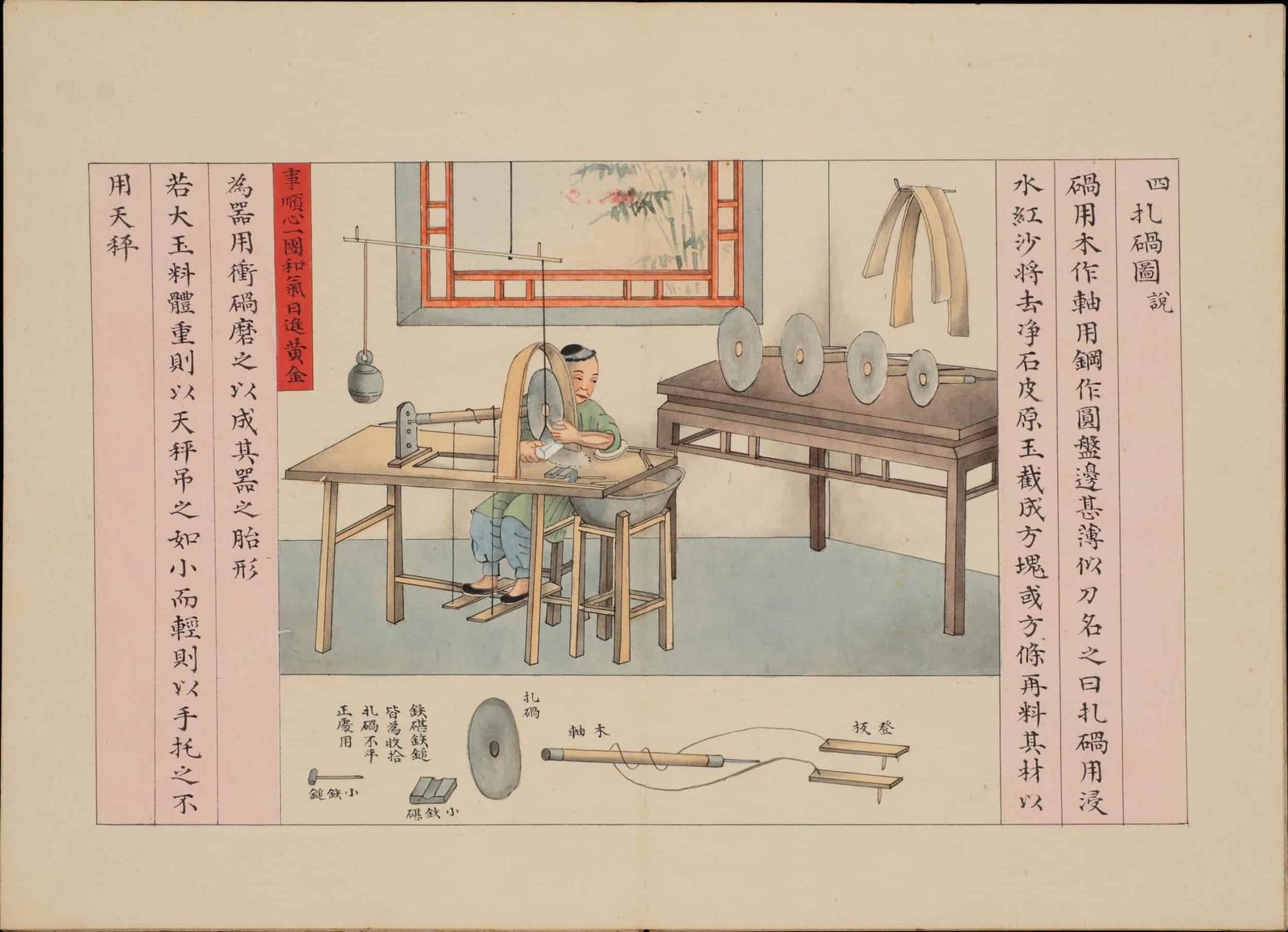

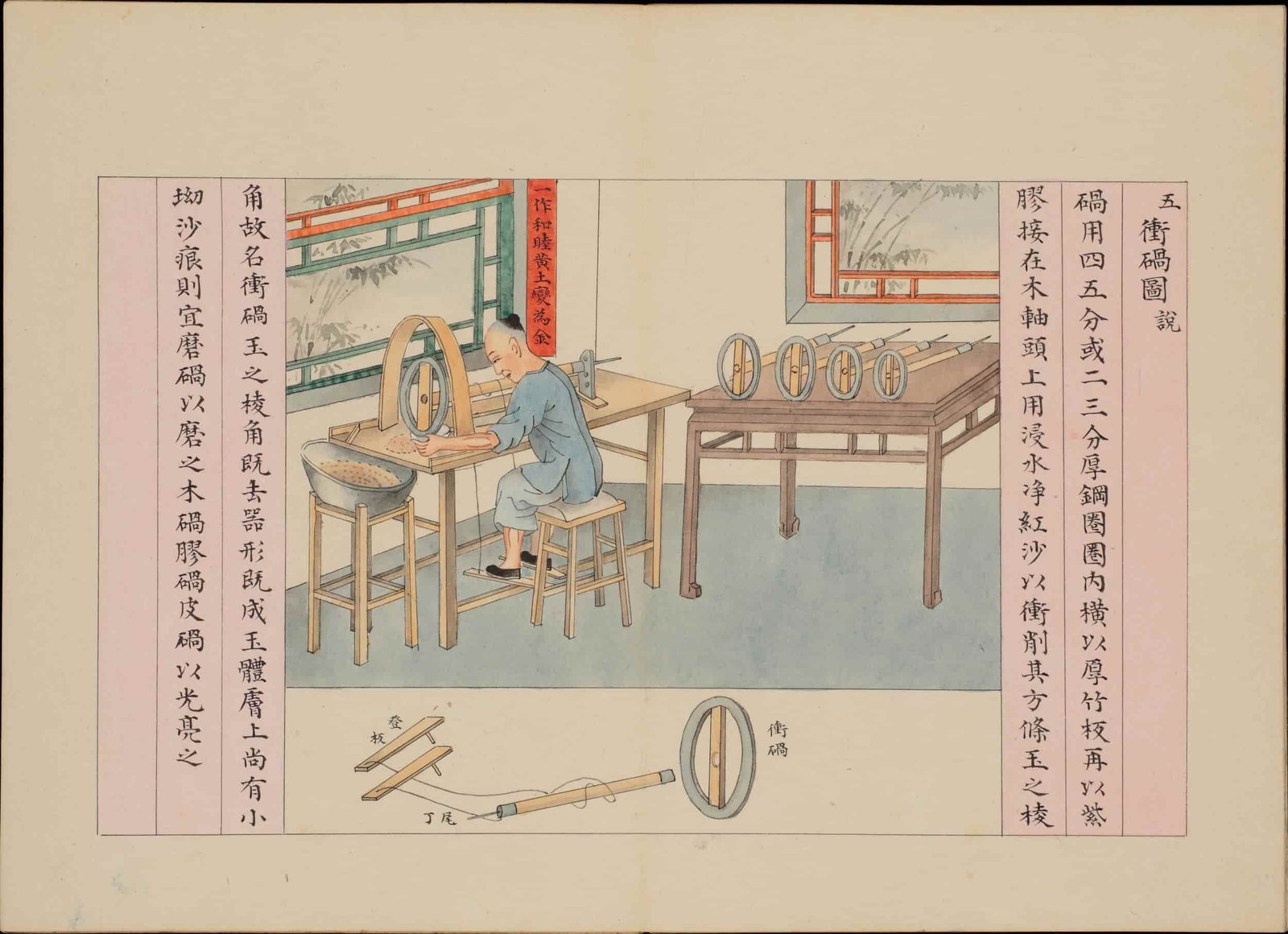

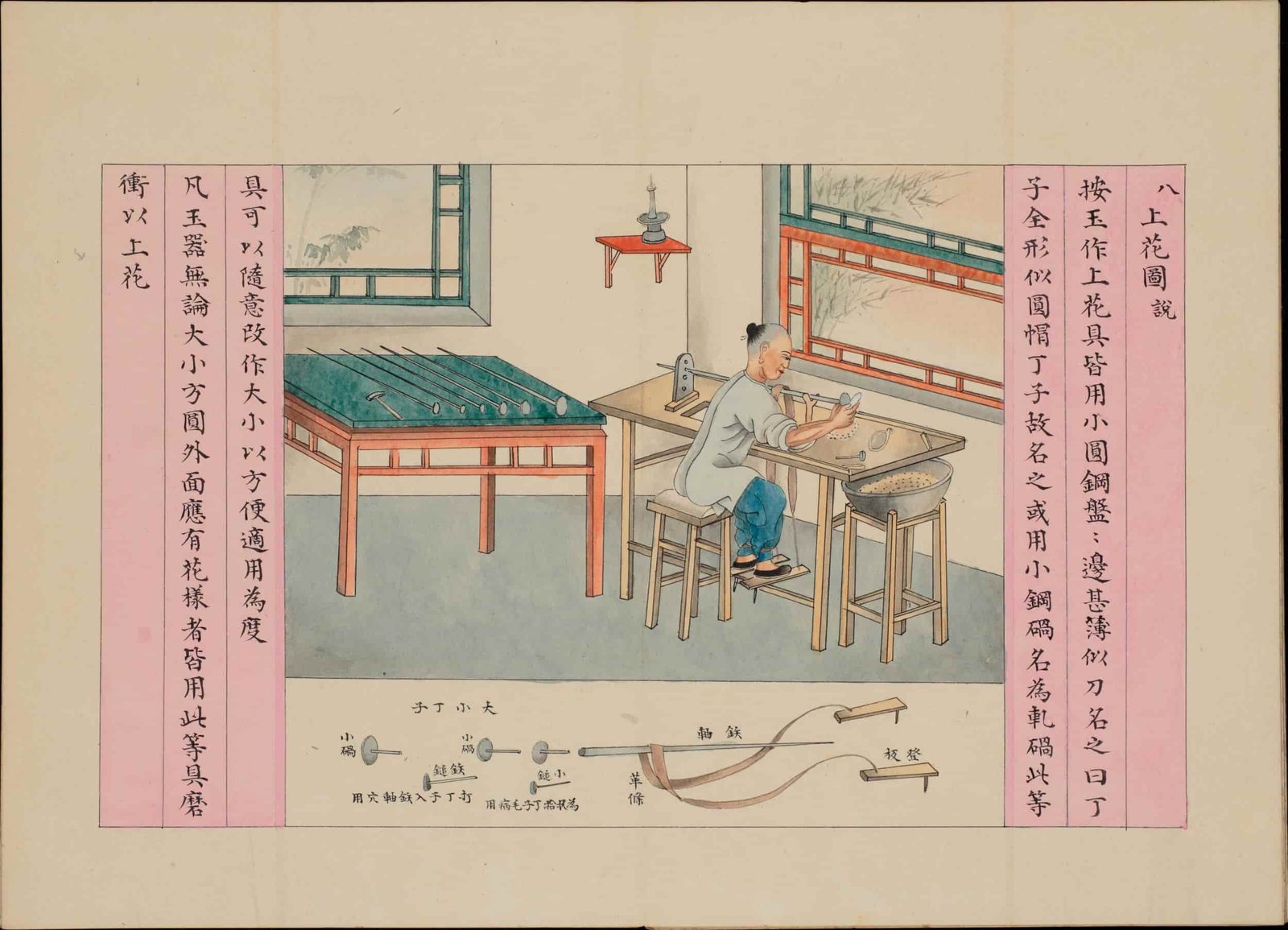

- Zhatuo (扎碢, Shaping with Discs)

- Tools: Gangpian (钢片, steel disc), Hongsha (红沙, red corundum sand).

- Innovation: Steel discs (ancestors of modern diamond-coated wheels) allowed precise shaping of intricate forms like bi discs and cong tubes.

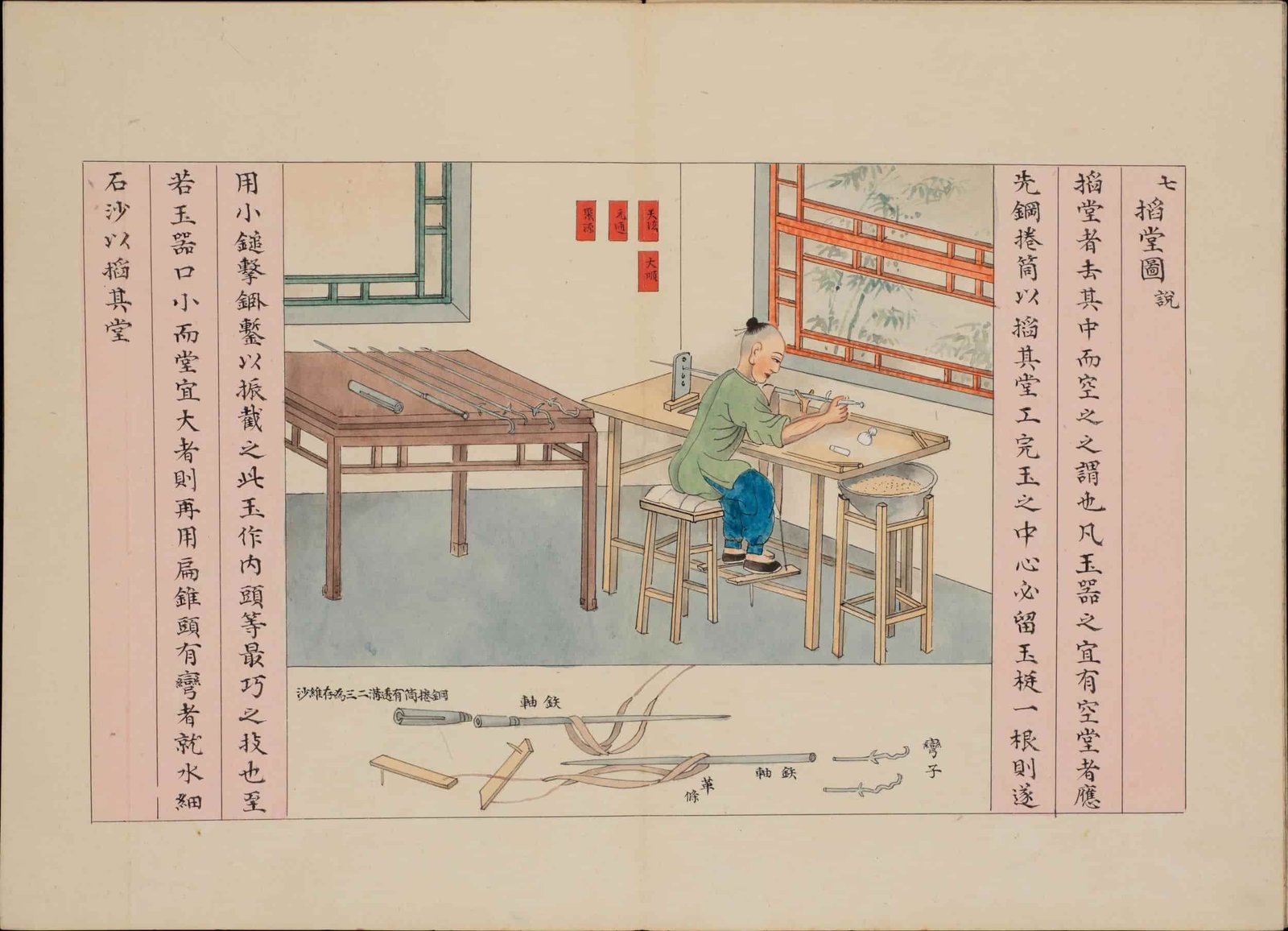

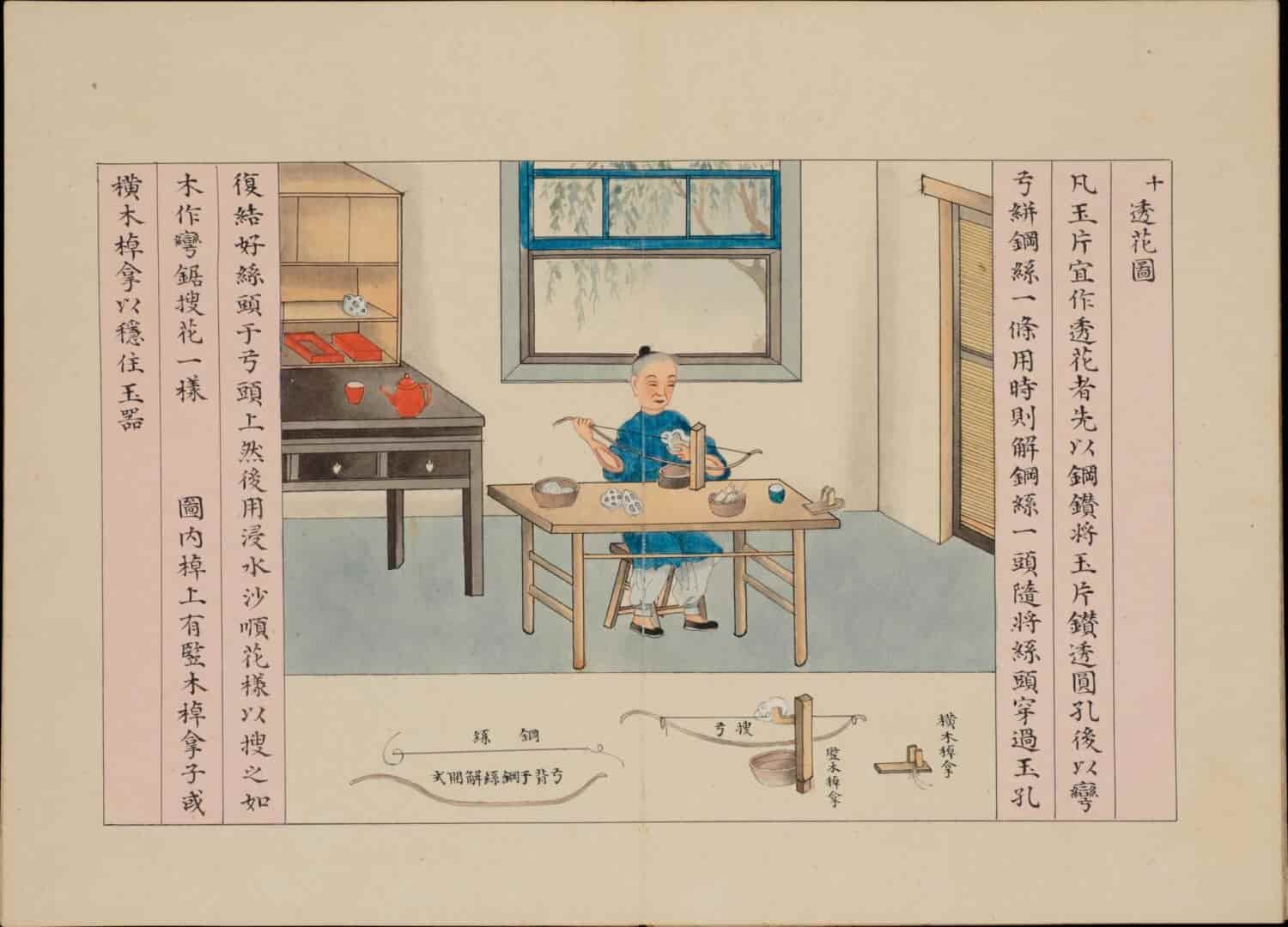

- Toutang (掏堂, Hollowing)

- Tools: Gangjuantong (钢卷筒, steel drill tube), Wanzi (弯子, curved chisel).

- Technique: Artisans hollowed jade vessels (e.g., zun 樽 wine vessels) using bow-driven drills, a method later mirrored in Mesopotamian lapidary work.

Cultural Context

- Jade’s Symbolism: The manual emphasizes jade’s role as “the essence of Heaven and Earth” (天地精华), embodying Confucian virtues like benevolence (仁) and wisdom (智).

- Imperial Patronage: Qing emperors like Qianlong elevated jade carving to a state art, with workshops in Beijing’s Forbidden City producing ritual objects like the Jadeite Cabbage (翠玉白菜).

Translation Strategy

- Terminology:

- Retain pinyin for processes (e.g., Zhatuo) with tool explanations:

- Pituo (皮碢): Leather polishing wheel soaked in baoliao (宝料, polishing slurry).

- Contextualize idioms:

- “玉不琢,不成器” → “Jade unworked holds no virtue” (analogy: “A diamond in the rough”).

- Retain pinyin for processes (e.g., Zhatuo) with tool explanations:

- Visual Aids:

- Include a glossary mapping tools to modern equivalents:

Traditional Tool Modern Equivalent Jin Gang Zuan (金钢钻) Diamond-tipped drill bit Wan Gong (弯弓) Bow-driven lathe

- Include a glossary mapping tools to modern equivalents:

- Cultural Parallels:

- Compare Li Chengyuan’s Yuzuo Tu to Georgius Agricola’s De Re Metallica (1556), highlighting shared themes of craftsmanship documentation.

Legacy & Modern Revival

- Intangible Heritage: Beijing jade carving was listed as national intangible cultural heritage in 2008, with masters like Zhang Sencai blending traditional techniques (e.g., yinxian diao 阴线雕 relief carving) with Māori-inspired motifs.

- Exhibitions: Recent shows like Jade Carving Masterpieces at the Chen Clan Academy (2025) showcase works like Flourishing—a jade bonsai integrating Russian nephrite and Māori whale-tail symbolism.

Appendices

- Li Chengyuan’s Preface:

“玉工之技,贵在因材施艺” (“The jade artisan’s skill lies in adapting to the material’s nature”).

- Bushell’s Notes: The British scholar praised the manual’s “scientific rigor” in his 1895 treatise Chinese Art.

For digitized pages, visit National Library of China’s Rare Books Collection.

评价

目前还没有评价