Farewell to Winter and Welcoming Auspiciousness: An Illustrated Album

Overview

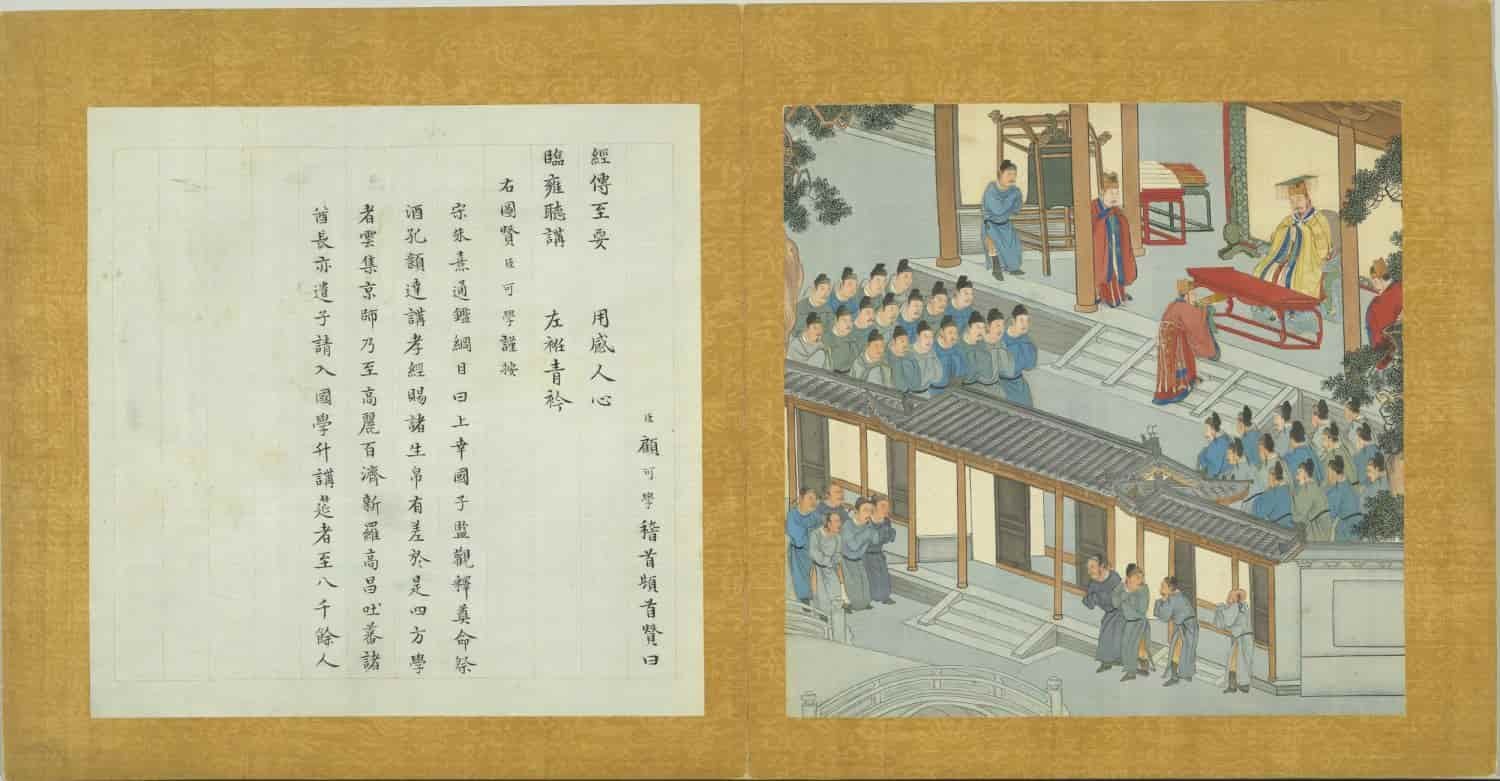

This 8-panel Qing Dynasty album, Farewell to Winter and Welcoming Auspiciousness (Jiàn Là Yíng Xiáng Tú Cè), painted by Dong Gao (董诰, 1740–1818) in 1816 during the Jiaqing reign, vividly captures traditional Lunar New Year festivities in rural China. Housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, the album combines meticulous ink-and-color illustrations with poetic inscriptions by Emperor Jiaqing, blending folk customs with imperial symbolism. Each panel depicts rituals and celebrations from late winter to early spring, reflecting both agrarian life and Confucian values.

Translations and Cultural Context

Cover Inscription

“Farewell to Winter and Welcoming Auspiciousness” (餞臘迎祥)

- Cultural Note: The title encapsulates the transition from the old year (là, 腊, the 12th lunar month) to the new, emphasizing renewal and blessings.

Panel-by-Panel Translations

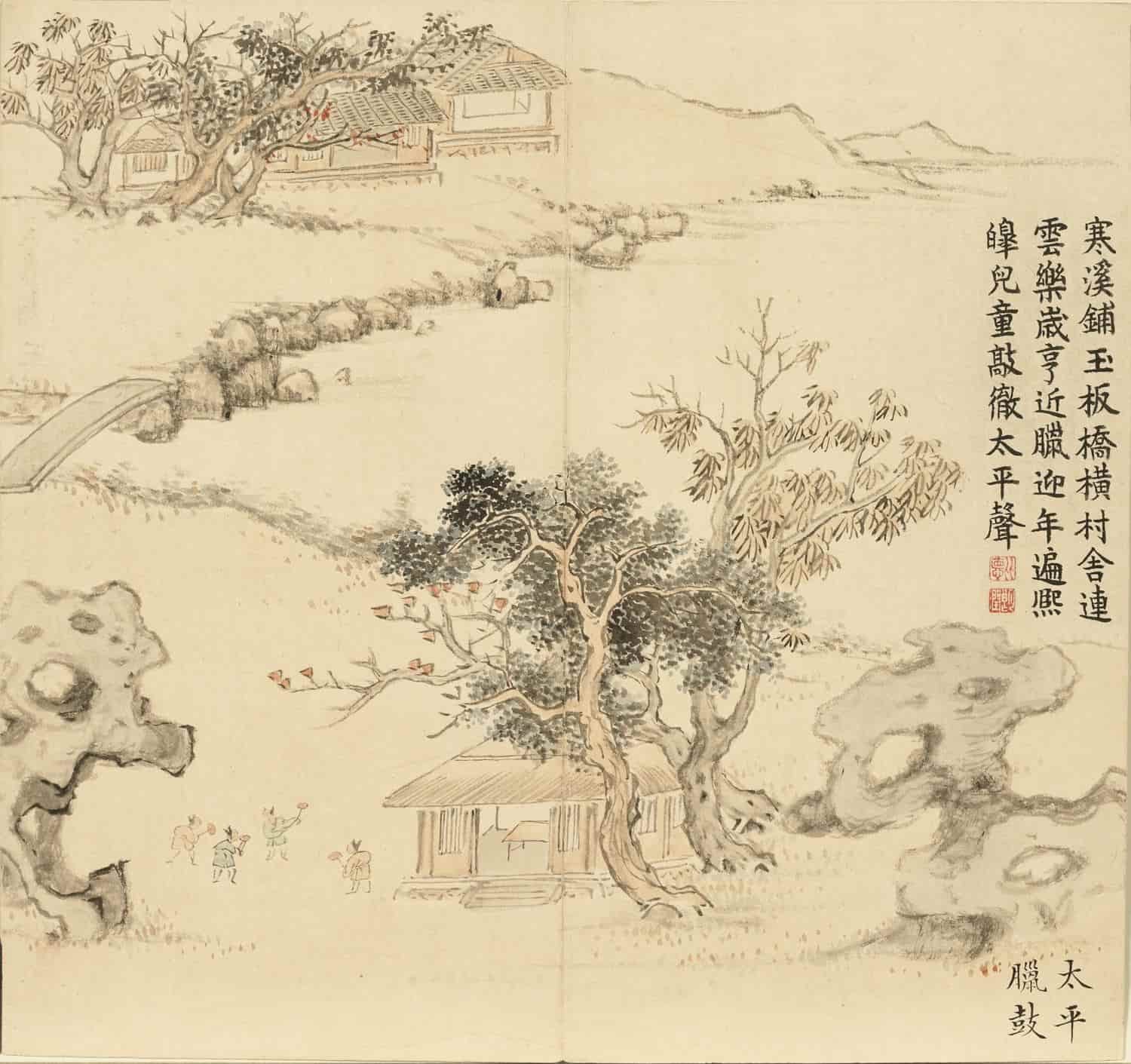

- Taiping Lagǔ (太平臘鼓, “Peace Drums of Winter”)

- Depiction: Children beat drums to herald the New Year.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Cold streams flow under jade-like bridges;

Villages rejoice in abundance.

Winter’s end brings universal cheer—

Children drumming peace, their voices clear. - Symbolism: Drums symbolize communal unity and the expulsion of misfortune.

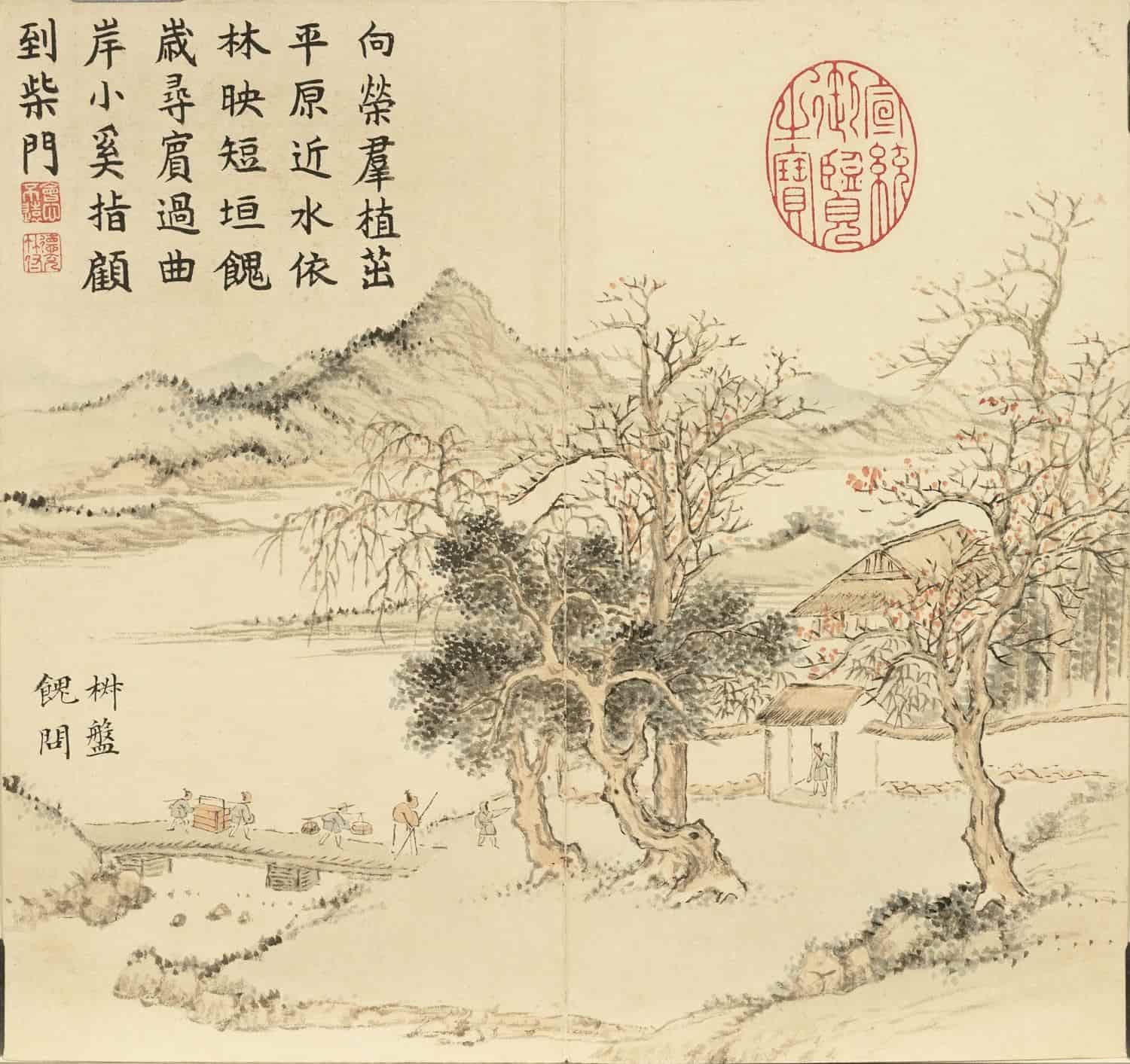

- Jiāo Pán Kuì Wèn (椒盤餽問, “Gifting Spiced Platters”)

- Depiction: Villagers exchange gifts across a riverside village.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Lush plants thrive by plain and stream;

Gifts cross winding paths to humble doors. - Cultural Note: Gift-giving (kuì suì, 餽歲) mirrors modern Lunar New Year customs of visiting relatives.

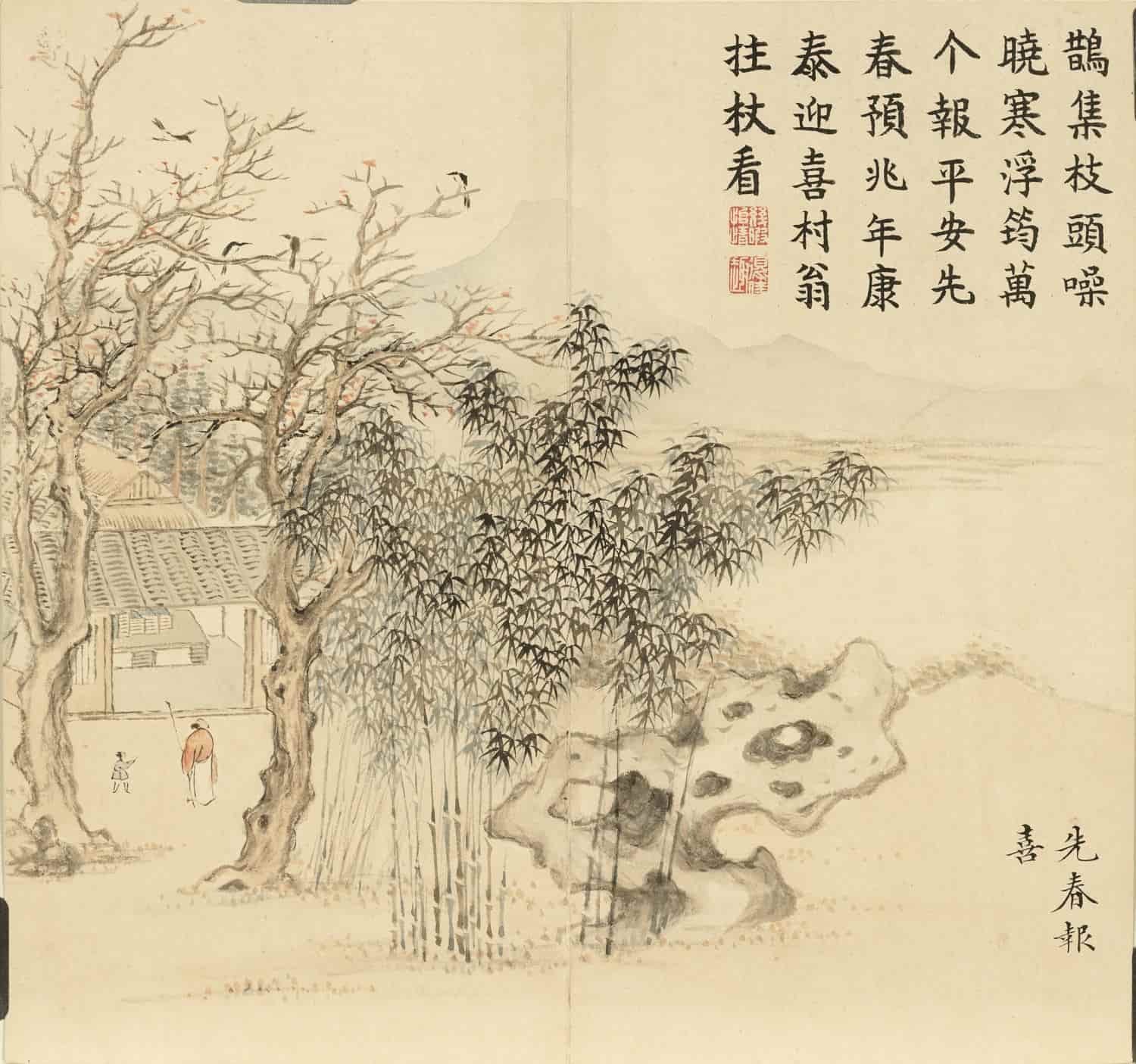

- Xiān Chūn Bào Xǐ (先春報喜, “Magpies Herald Spring”)

- Depiction: Magpies chirp on bamboo branches.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Magpies chatter in the frosty dawn;

Bamboo whispers peace, spring’s promise sworn. - Symbolism: Magpies symbolize joy, while bamboo represents resilience.

- Huáng Yáng Sì Zào (黃羊祀竈, “Yellow Sheep Sacrifice to the Kitchen God”)

- Depiction: A family offers a yellow sheep to Zao Shen (灶神), the Kitchen God.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Following Han traditions, yellow sheep honor the stove;

Five Zhou rites bless virtuous homes. - Historical Context: Based on a Han Dynasty legend where sacrificing yellow sheep brought wealth.

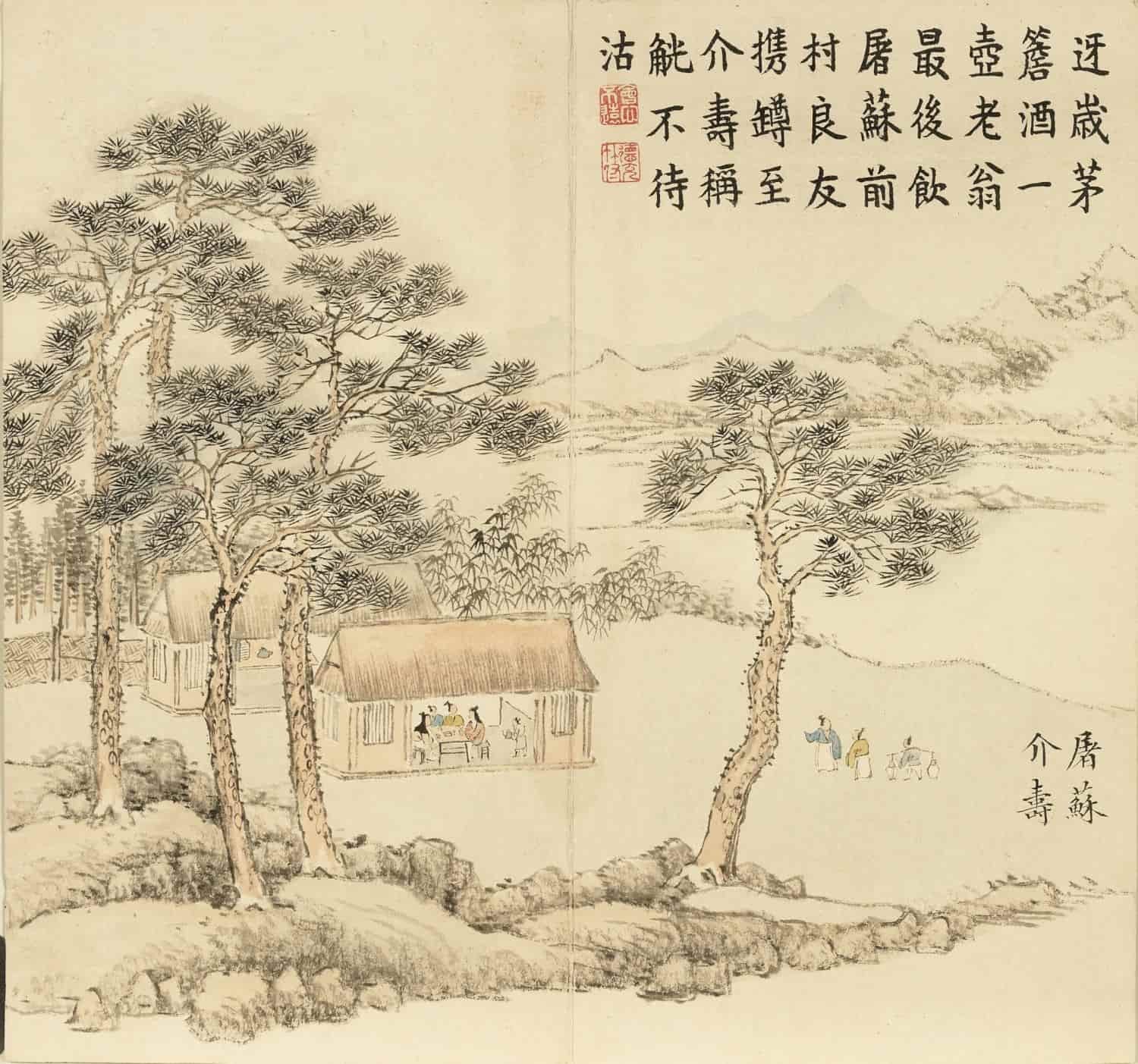

- Tú Sū Jiè Shòu (屠蘇介壽, “Longevity Wine at Dawn”)

- Depiction: Elders drink tusu wine (屠蘇酒), a medicinal liquor, on New Year’s Day.

- Emperor’s Poem:

In humble huts, wine greets the year;

Friends arrive, cups raised in cheer. - Cultural Practice: Drinking tusu wine, believed to ward off plagues, follows an age-reversed order—elders drink last.

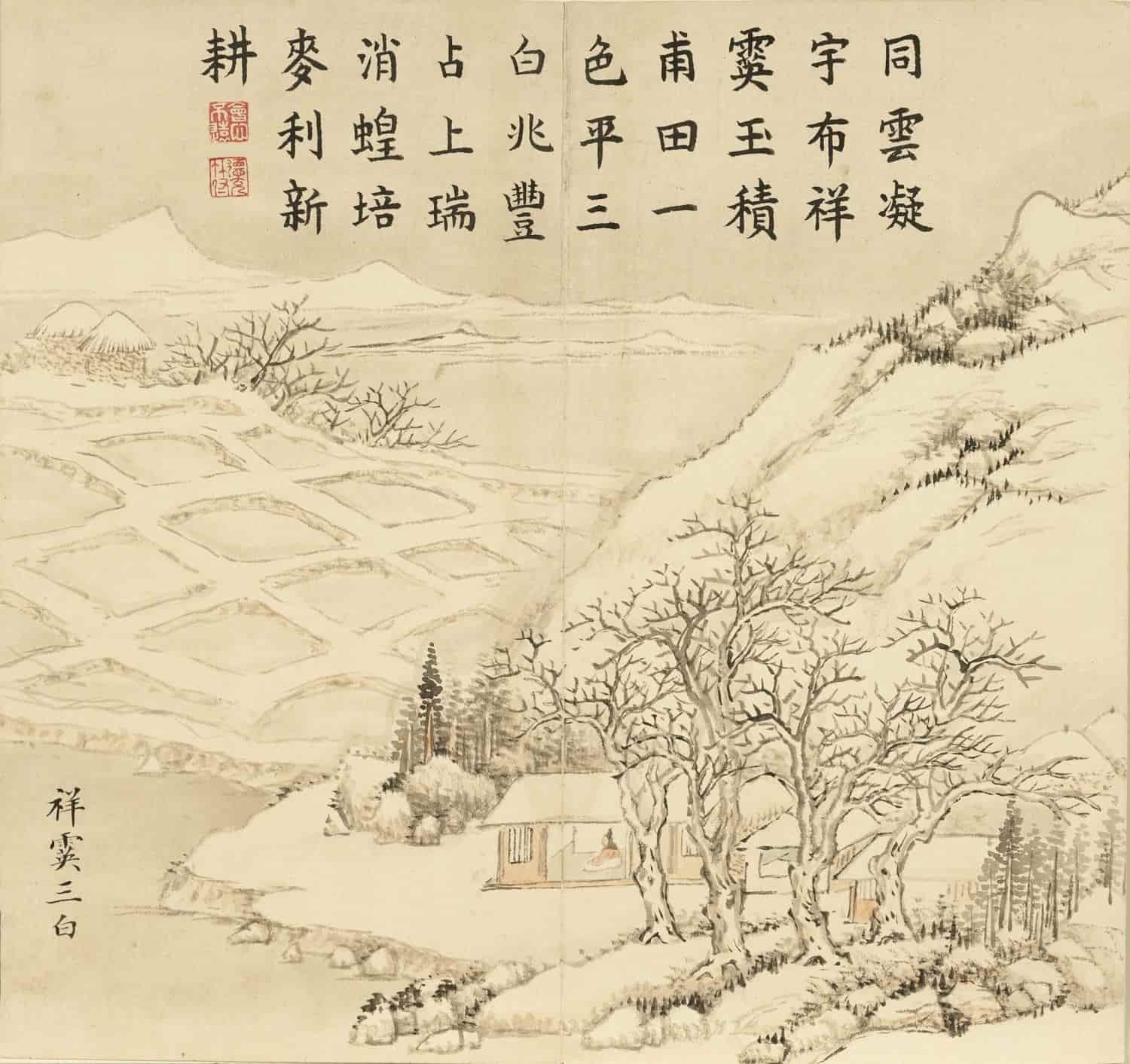

- Xiáng Yīng Sān Bái (祥霙三白, “Auspicious Snow for Bountiful Harvests”)

- Depiction: Snow blankets fields, foretelling agricultural prosperity.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Snow drapes the land in purest white;

Three layers promise wheat and respite. - Symbolism: “Three white snows” (sān bái, 三白) were believed to eliminate pests and nourish crops.

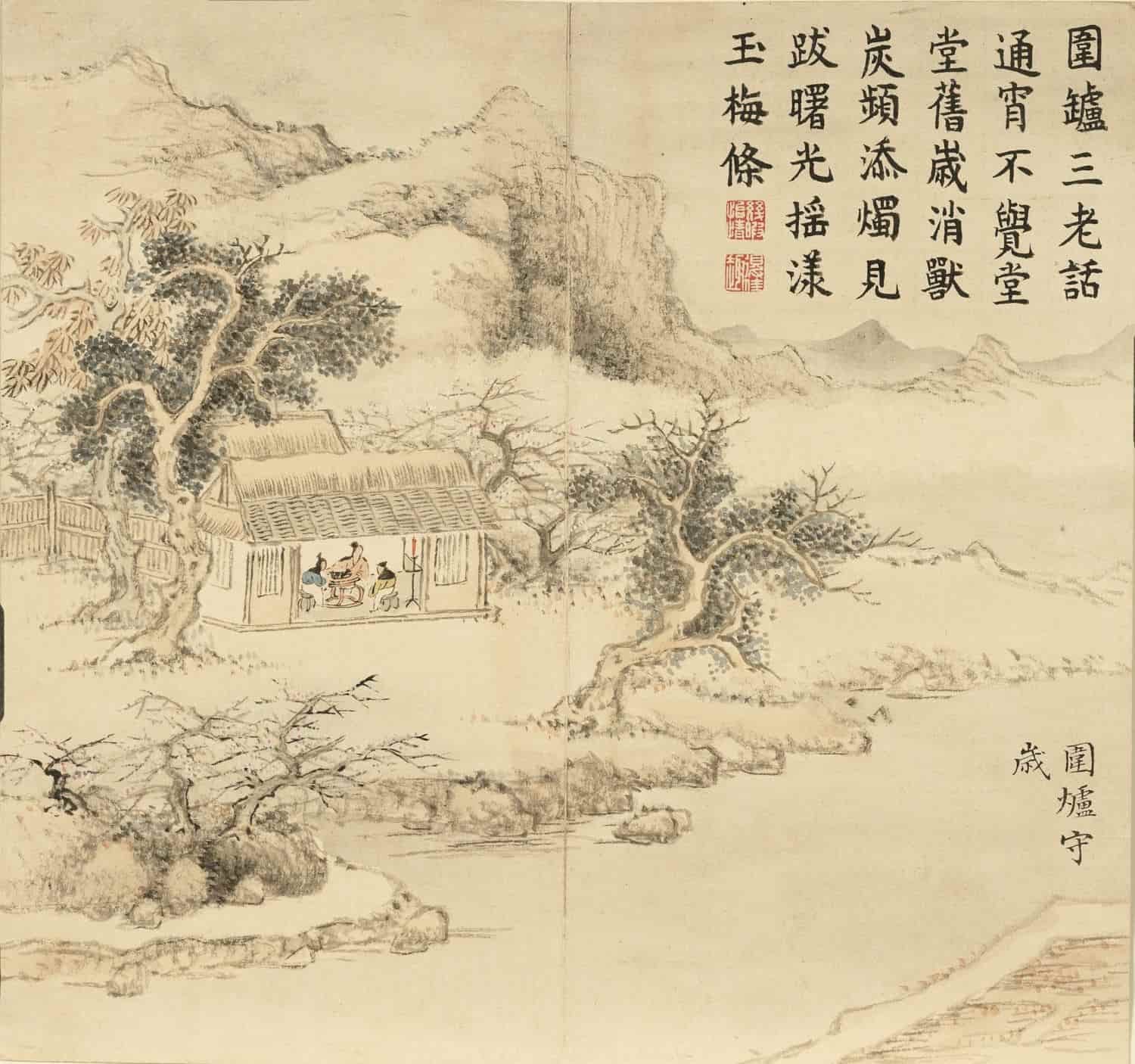

- Wéi Lú Shǒu Suì (圍爐守歲, “Vigil by the Hearth”)

- Depiction: Three elders converse by a stove through the night.

- Emperor’s Poem:

By the fire, old tales unfold;

Midnight passes, dawn’s light takes hold. - Tradition: Staying awake on New Year’s Eve (shǒu suì, 守歲) symbolizes guarding against misfortune.

- Jí Bào Yíng Sháo (吉爆迎韶, “Firecrackers Welcome Spring”)

- Depiction: Villagers light firecrackers to greet the new season.

- Emperor’s Poem:

Firecrackers roar, evil spirits flee;

Young and old embrace spring’s decree. - Symbolism: Firecrackers (biān pào, 鞭炮) drive away malevolent forces and invite luck.

Artist Background

Dong Gao (董诰)

- Life: A scholar-official from Fuyang, Zhejiang, Dong served as a Grand Secretary under Emperor Qianlong and Jiaqing. He was renowned for his landscapes and calligraphy, inheriting his father Dong Bangda’s (董邦達) artistic legacy.

- Style: His paintings blend Song-Yuan dynasty techniques with Qing realism, emphasizing harmony between humans and nature.

- Legacy: Posthumously honored as Wen Gong (文恭, “Cultured and Respectful”), his works bridge imperial ideology and folk culture.

Historical and Cultural Significance

- Festival Origins: The rituals depicted, such as sacrificing to the Kitchen God and drinking tusu wine, date to the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE). By the Qing era, these practices had evolved into public celebrations.

- Imperial Propaganda: Emperor Jiaqing’s poems reframe folk customs as symbols of benevolent governance, particularly after the White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804).

- Material Artistry: The album’s butterfly binding (蝴蝶装) and delicate inkwork on paper (23.9 × 25.4 cm) exemplify Qing craftsmanship.

Modern Relevance

- Exhibitions: Featured in Taipei’s Festivals of the Qing Court (2025), the album inspires contemporary Lunar New Year decorations and museum displays.

- Cultural Revival: Traditions like tusu wine and firecracker rituals are revived in Zhejiang and Fujian during modern Spring Festivals.

评价

目前还没有评价