Manual of Ceramic Production Album” (陶瓷谱图冊 / Táocí Pǔ Tú Cè)

—A Qing Dynasty Illustrated Guide to Jingdezhen Porcelain (17th–18th Century)

Overview

This 14-panel silk-scroll album, housed in Taipei’s National Palace Museum, documents the 12-step imperial porcelain production process in Jingdezhen—China’s “Porcelain Capital” since the Song Dynasty. Commissioned by the Qing court, it combines gongbi (工笔, fine-line) paintings with technical annotations, serving as both an artistic treasure and a practical manual for artisans. The album reveals how raw kaolin clay from Qimen Mountain transformed into world-renowned blue-and-white (qinghua) and polychrome (wucai) ceramics through rituals of earth, fire, and imperial decree.

Full Translation & Contextual Insights

Preface: “Record of Jingdezhen Ceramics

Translated from Classical Chinese:

Jingdezhen lies 300 li (150 km) from Jiujiang, under Fuliang County, Raozhou Prefecture. In 1369 (Hongwu 2nd year of the Ming), imperial kilns were established here under eunuch supervision. After the Qing dynasty’s rise, oversight shifted from local magistrates (1654) to the Ministry of Works, then to the Imperial Household Department (Yongzheng era). By Qianlong’s reign (1736–1795), Jiujiang customs officials managed production. Clay from Qimen, glaze minerals from Yunnan-Zhejiang, and strict protocols—no step skipped or rushed—yielded tribute wares rivaling Song masterpieces (Ding, Ru, Guan, Ge). Thus, this manual preserves Jingdezhen’s legacy.

Production Steps with Technical & Cultural Notes

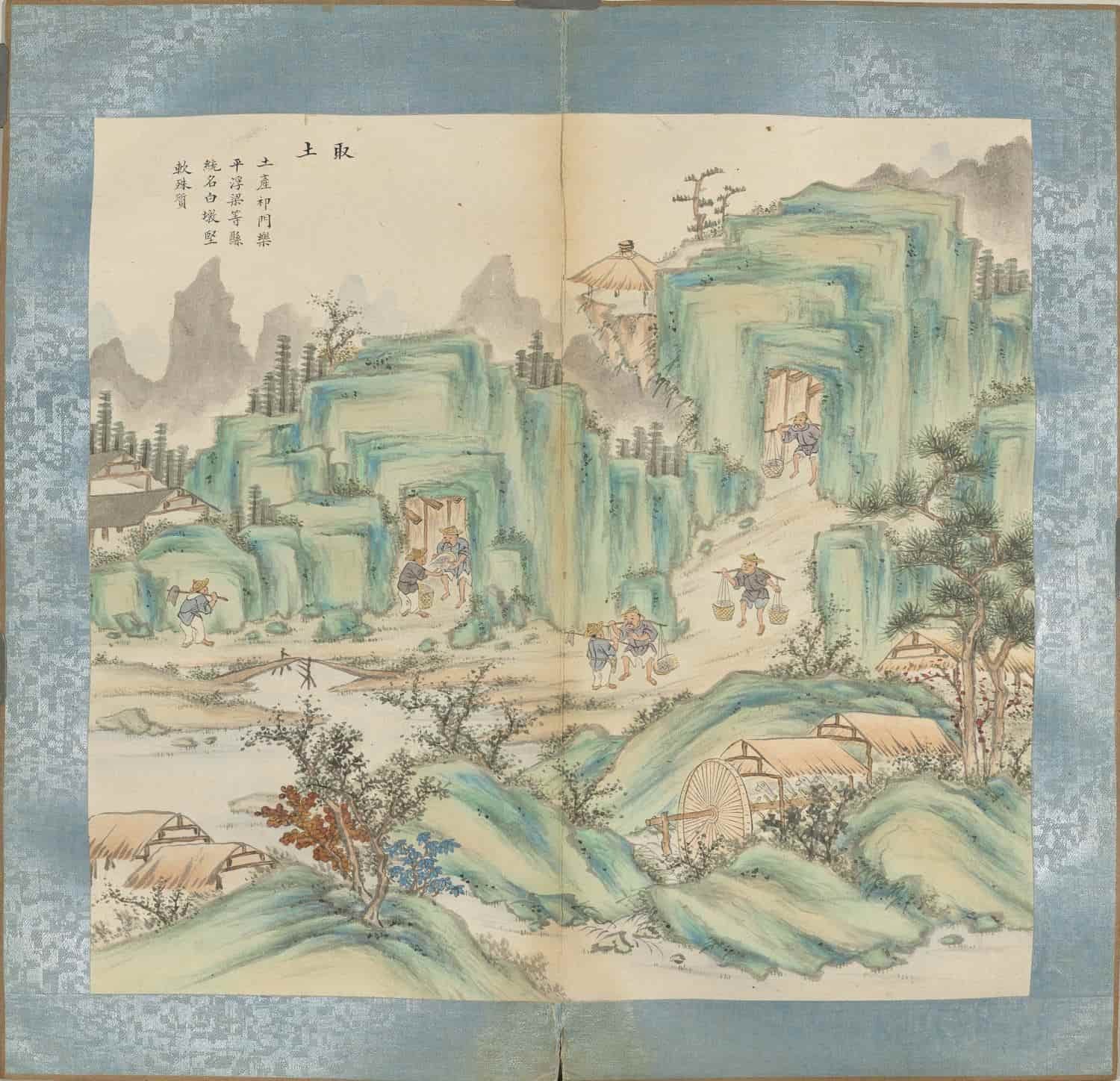

取土 (Extracting Clay)

Translation: Clay is sourced from Qimen, Leping, and Fuliang—all called ‘white loam’ (kaolin) with varying hardness.

Science: Kaolin’s low iron content enabled Jingdezhen’s iconic translucent porcelain.

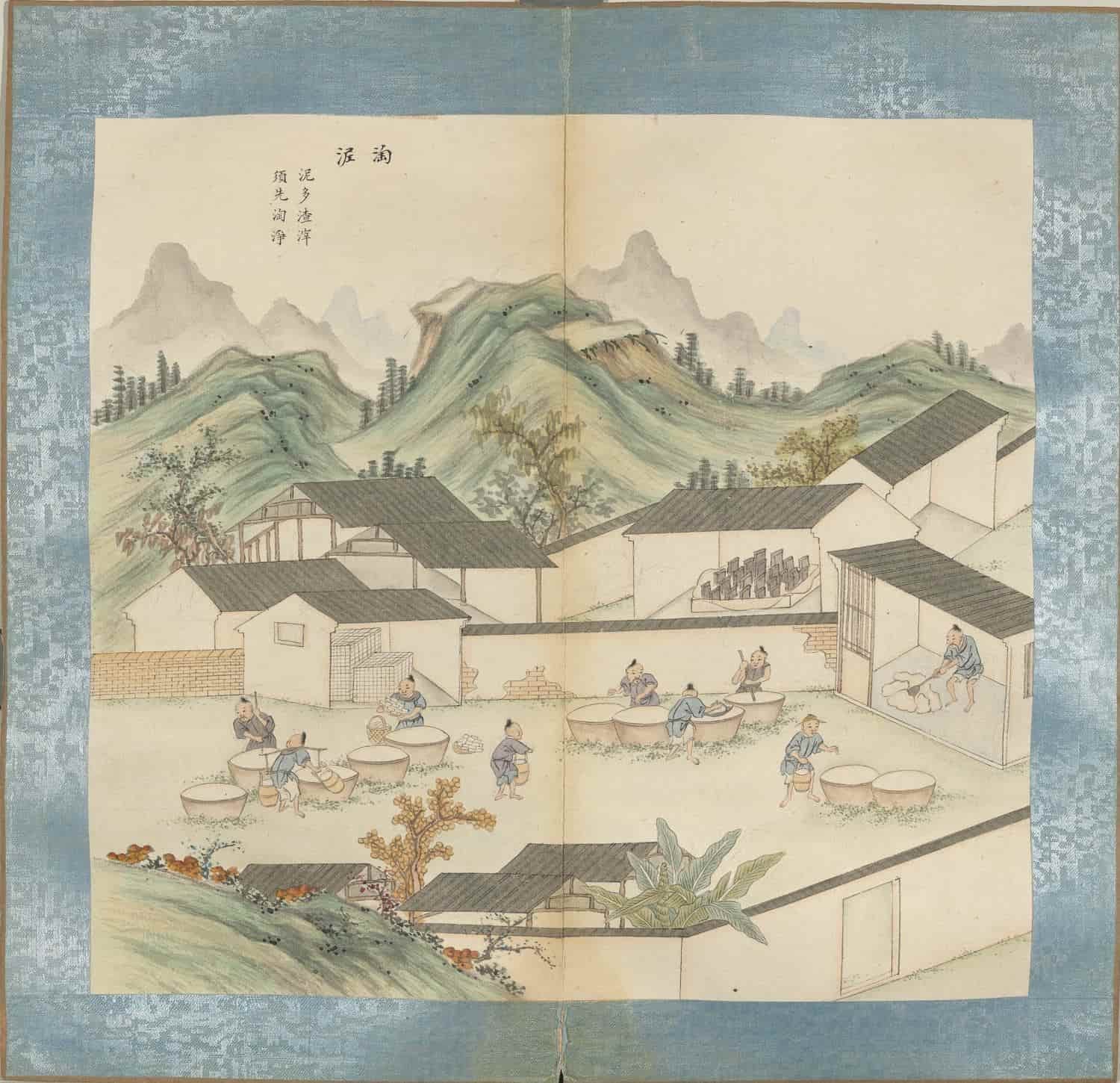

淘泥 (Purifying Clay)

Translation: Impure clay is washed in sedimentation pools.

Process: Workers used tiered tanks to filter grit—a technique unchanged since the Song.

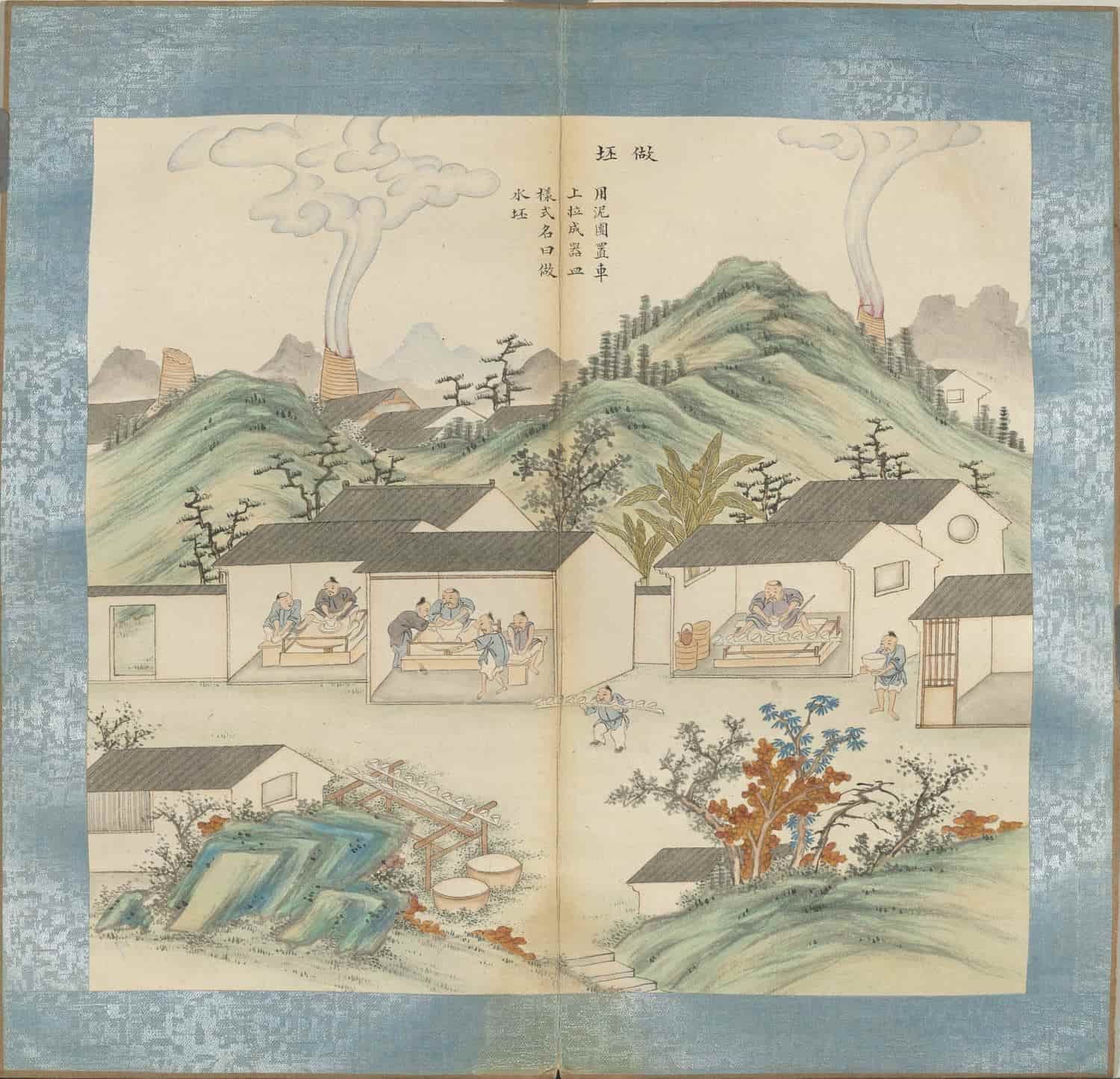

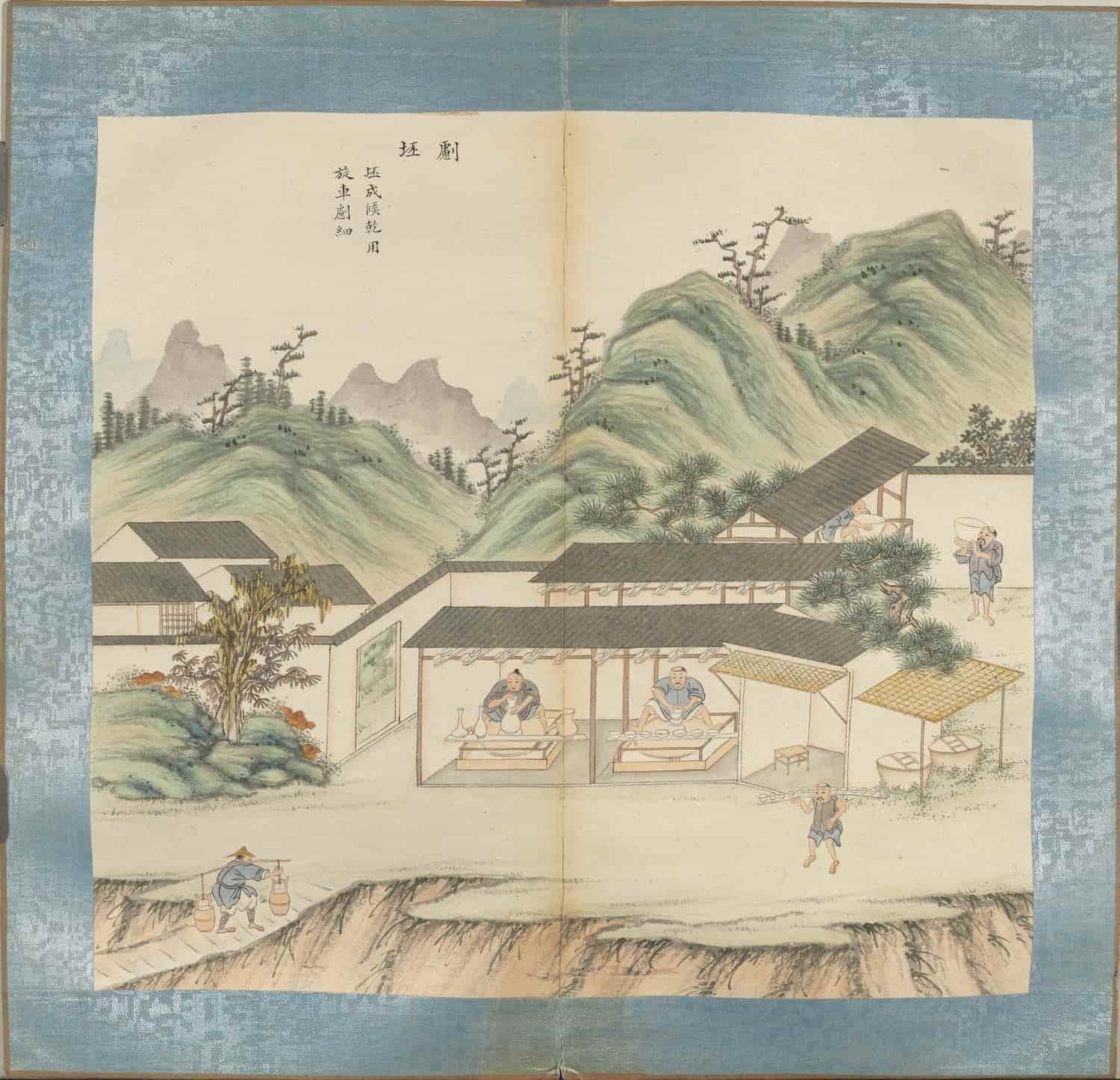

做坯 (Forming the Body)

Translation: A clay lump is thrown on a potter’s wheel into vessel shapes (shuǐ pēi 水胚).

Tool: The kick-wheel (lún chē 轮车) allowed symmetrical bowls at 200 RPM.

利坯 (Refining the Body)

Translation: Dried rough bodies are lathed (xuánchē 旋车) to precision.

Skill: 0.1-mm thickness tolerance for eggshell porcelains.

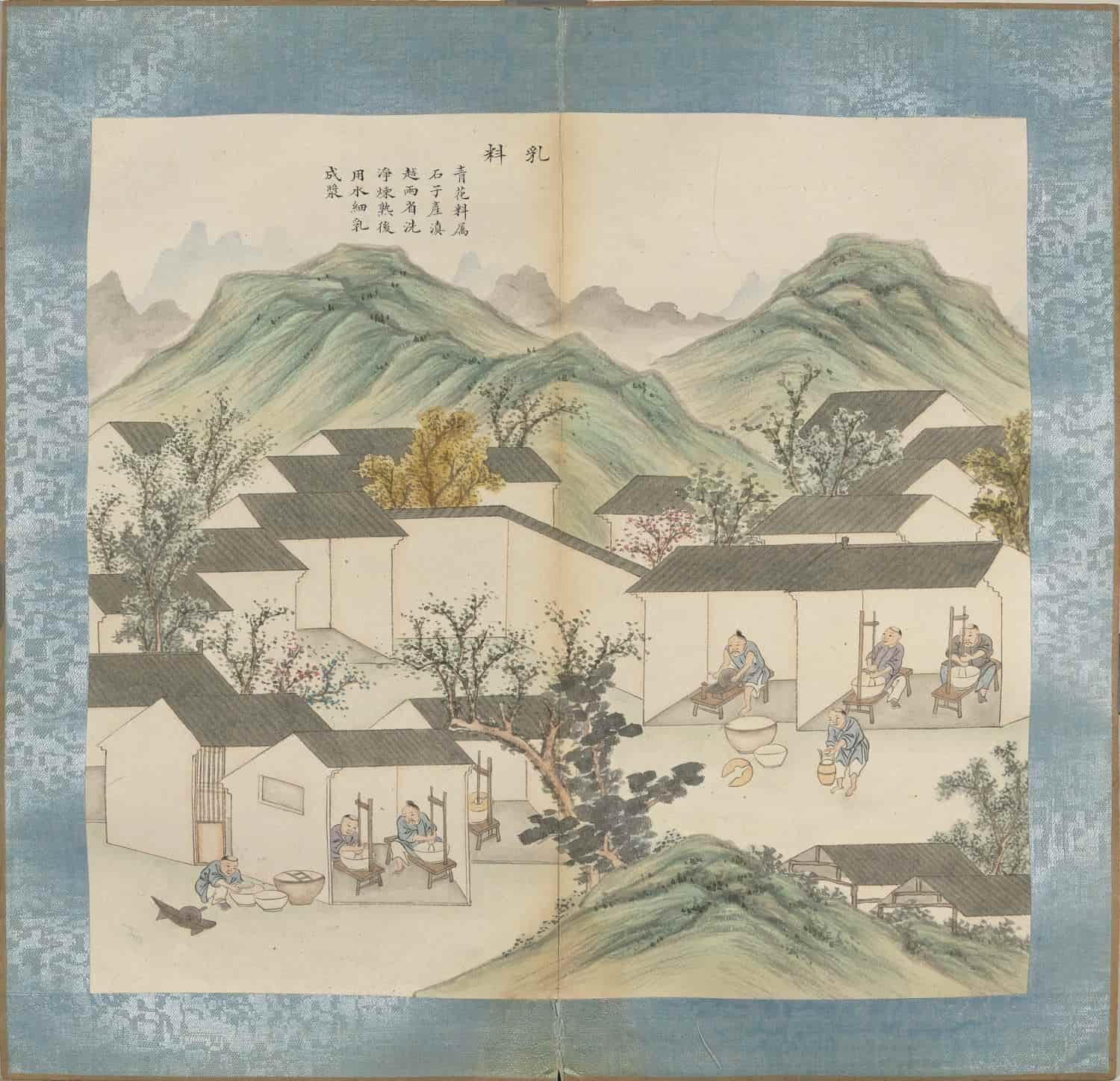

乳料 (Preparing Pigments)

Translation: Yunnan cobalt (伊斯兰蓝 ‘Islamic blue’) is calcined and ground into slurry.

Trade: Cobalt traveled 2,000 km via Tea-Horse Road from Muslim miners.

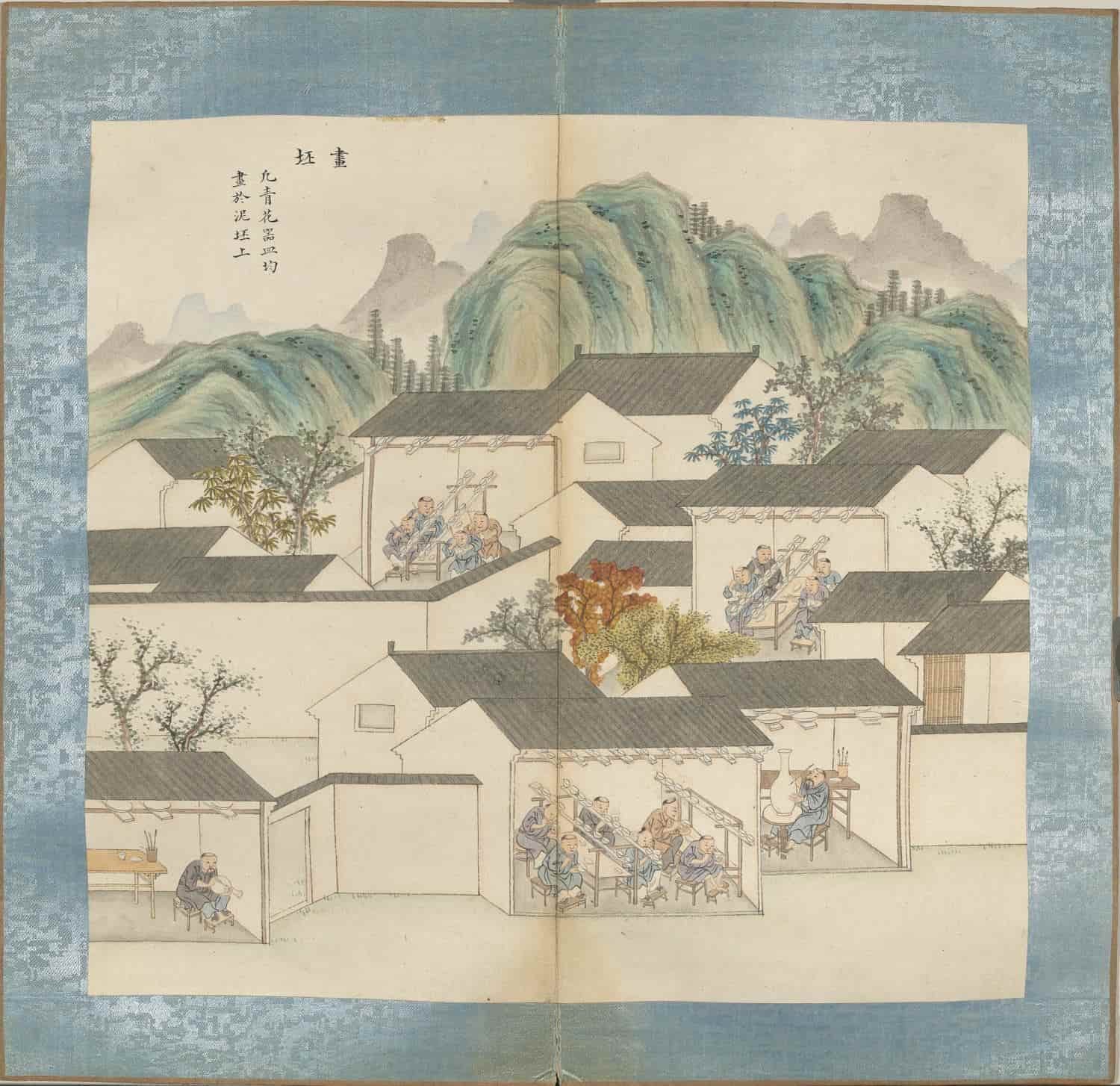

画坯 (Painting the Body)

Translation: Blue-and-white designs are brushed onto dry bodies.

Artistry: Master painters used wolf-hair brushes for freehand dragons—a 10-year apprenticeship skill.

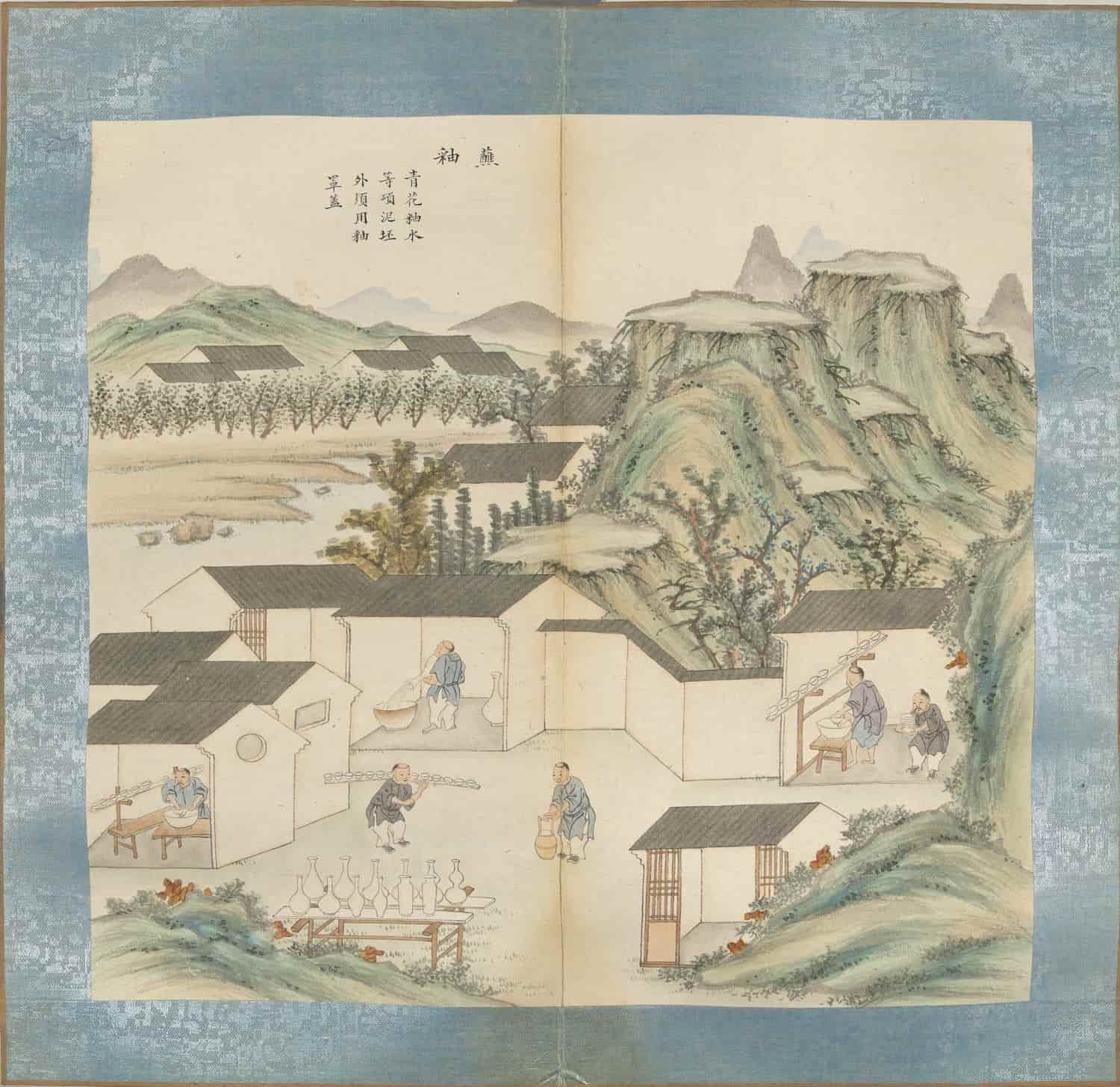

蘸釉 (Glazing)

Translation: Bodies are dipped in glaze (ash + limestone) for glassy finishes.

Chemistry: 1,300°C firing fused SiO₂-Al₂O₃ into yingqing (影青) jade-like surfaces.

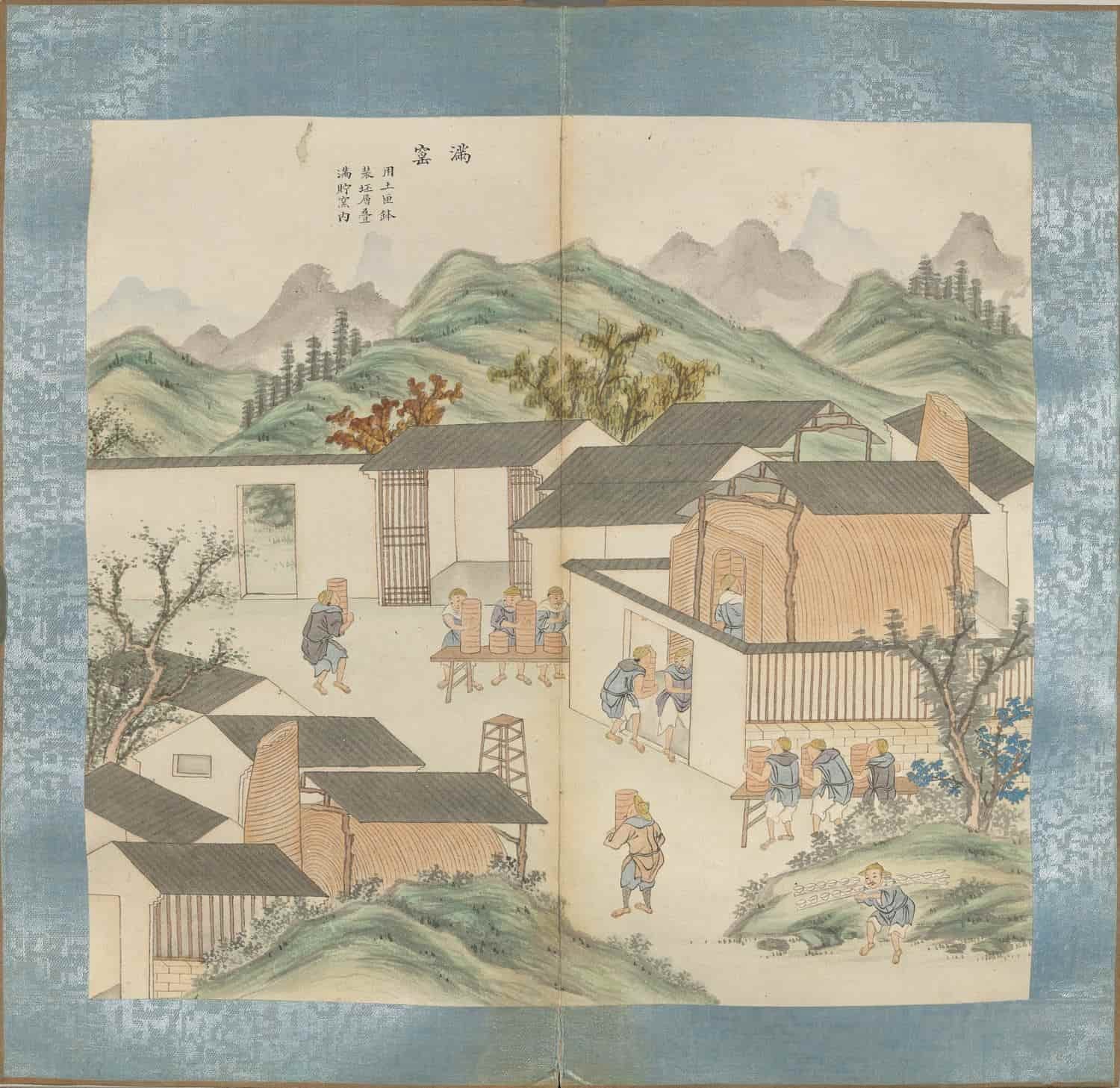

满窑 (Loading the Kiln)

Translation: Wares are stacked in saggers (clay containers) within zhenyao (镇窑) kilns.

Engineering: 18-meter-long dragon kilns held 25,000 pieces per firing.

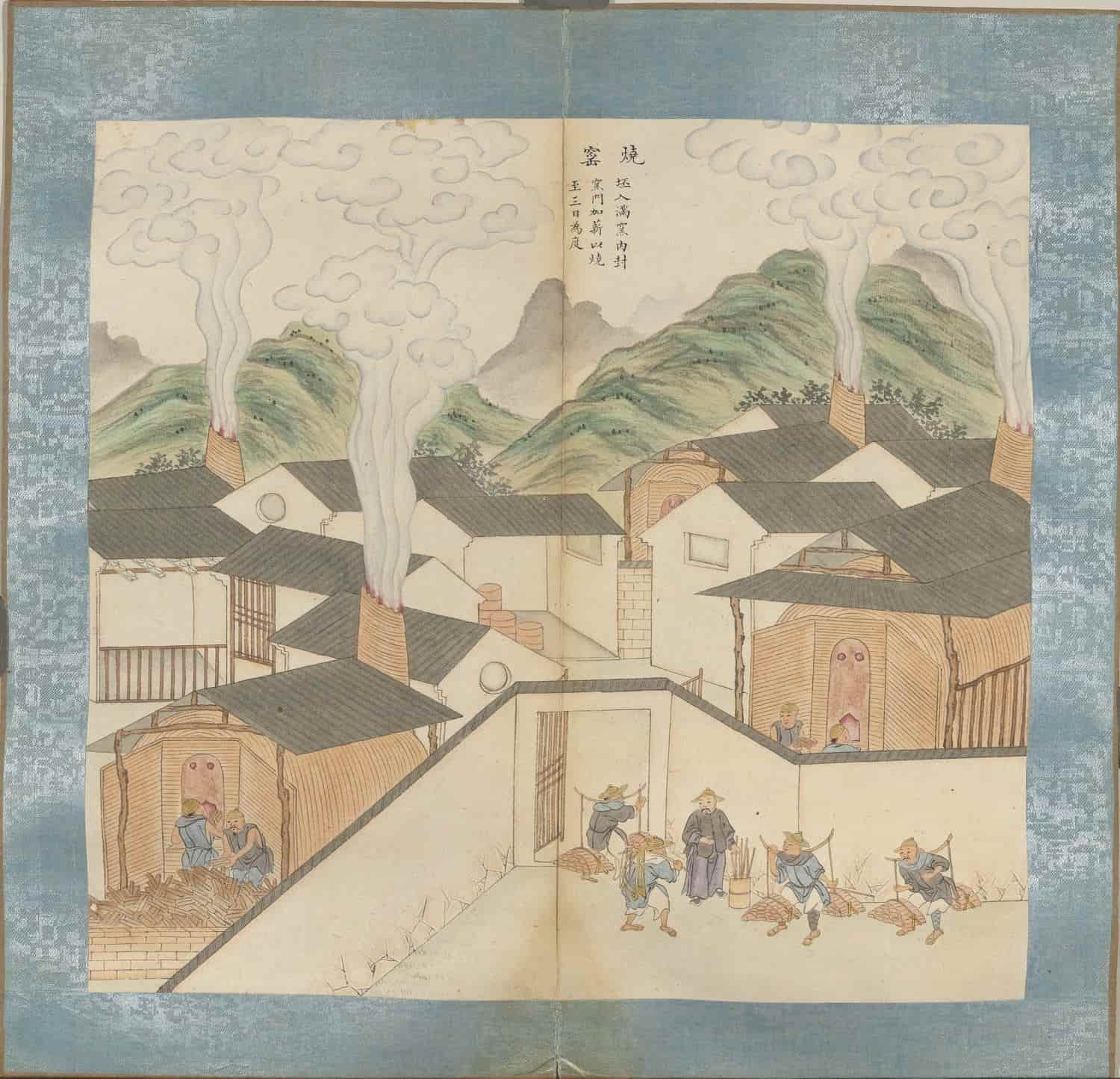

烧窑 (Firing)

Translation: Kilns are sealed and fueled with pine for 72 hours.

Labor: Teams of 30 stoked fires in 4-hour shifts, guided by “kiln gods”.

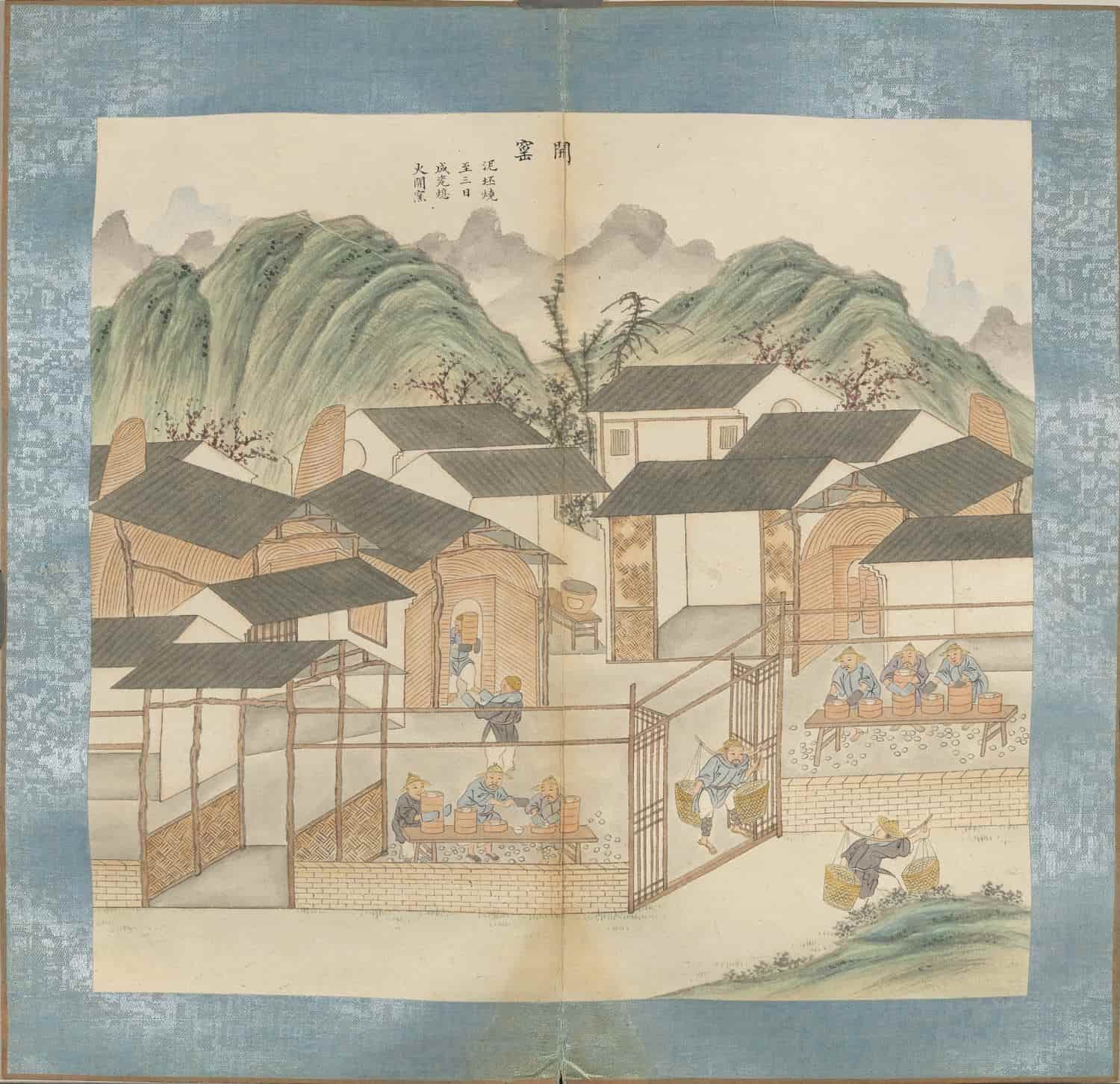

开窑 (Unloading)

Translation: After cooling, saggers are cracked open to reveal瓷器 (cíqì).

Risk: 30% loss rate from warping; flawless pieces marked with reign seals.

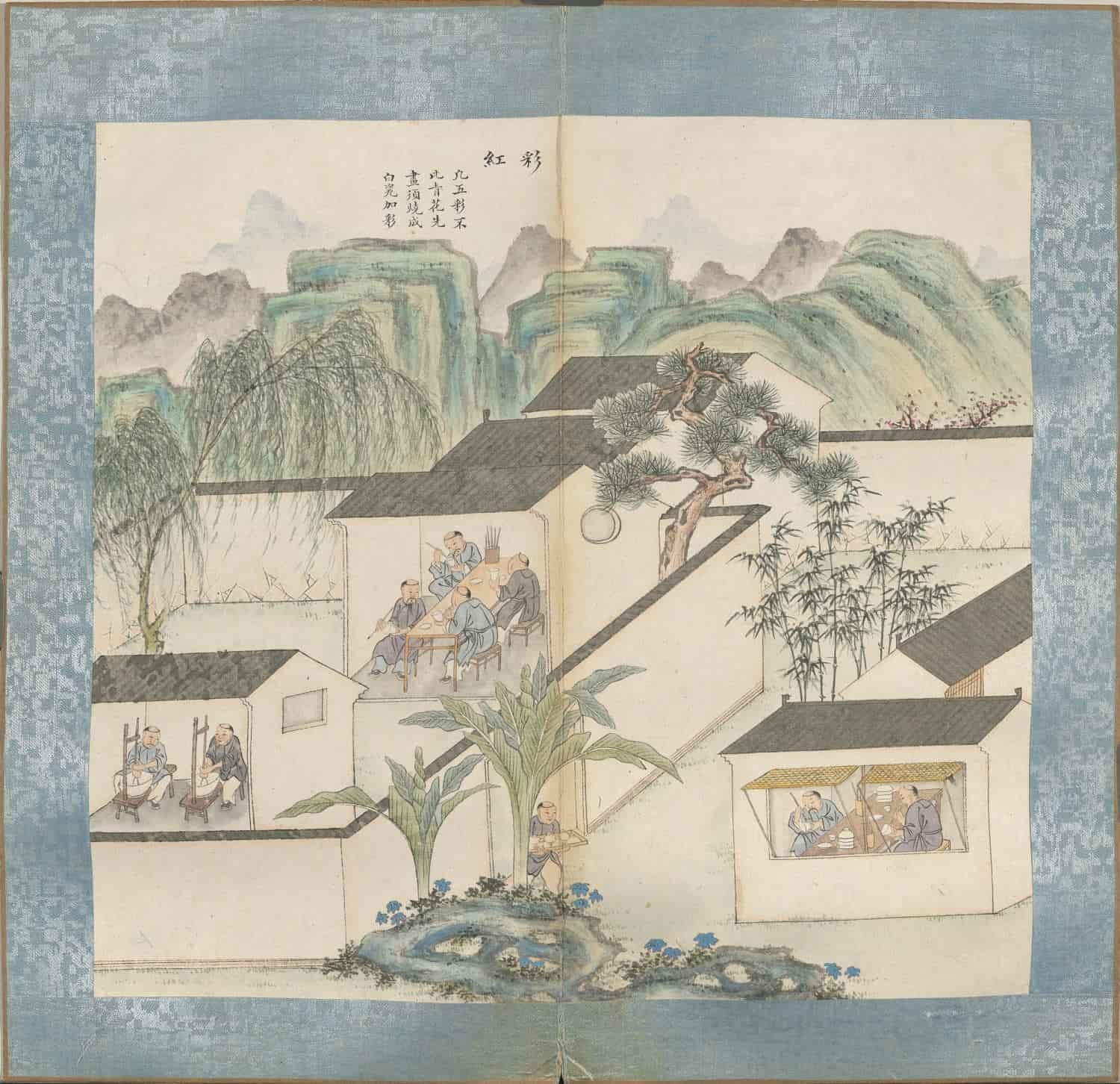

彩红 (Polychrome Painting)

Translation: “Enamels (famille verte) are added to fired whiteware.”

Innovation: Lead-tin yellows and European-derived pinks enriched Qing palettes.

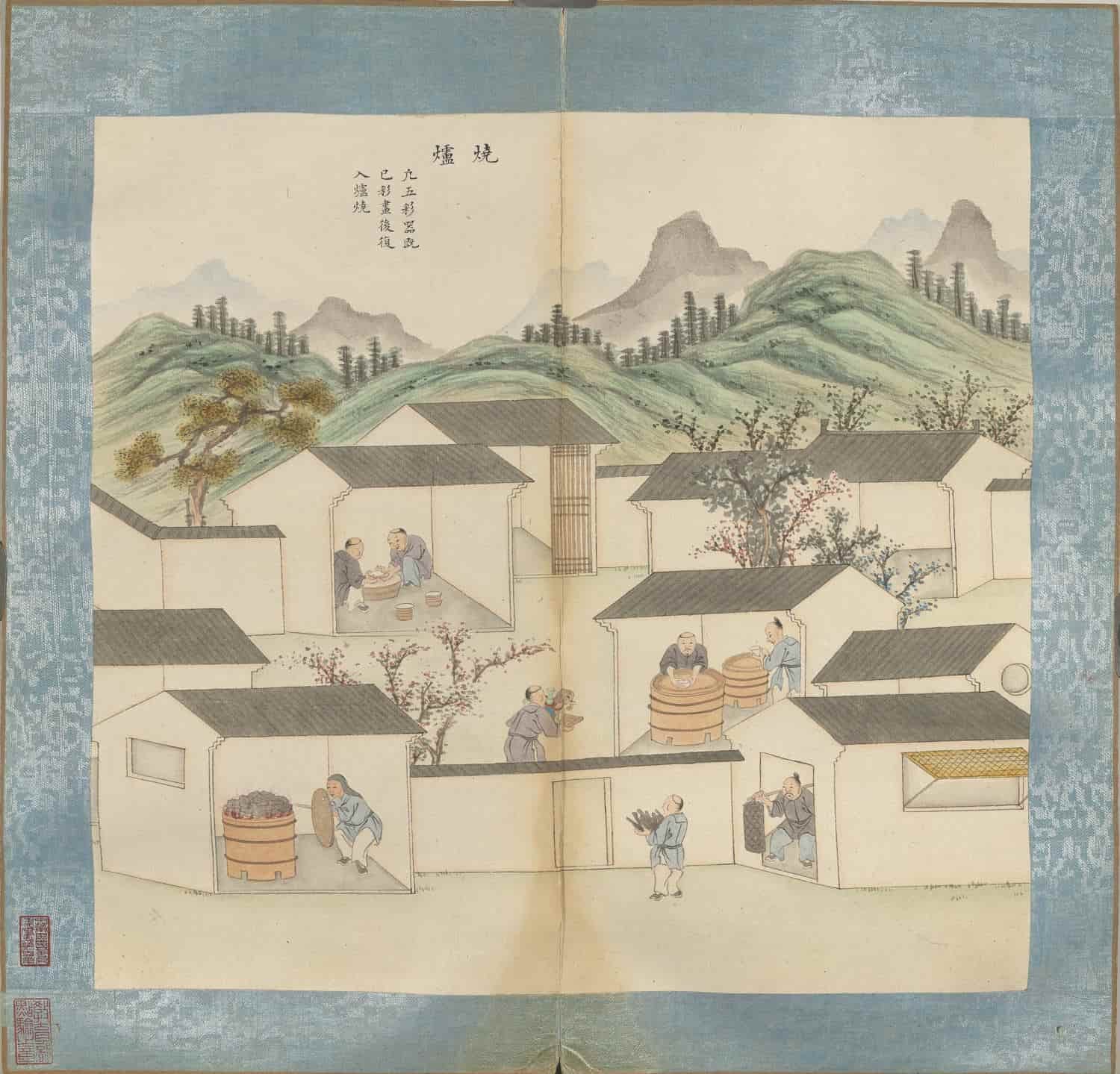

烧炉 (Enamel Firing)

Translation: Painted wares are refired at 800°C to fix colors.

Precision: Lower heat preserved delicate pinks from Ming Dynasty recipes.

Legacy & Global Influence

UNESCO Heritage: These steps underpin Jingdezhen’s 2006 intangible cultural heritage status.

Cross-Cultural Impact: Jesuit copies inspired Meissen (1710) and Sèvres (1756) porcelain.

Modern Revival: Artists like Liu Jianhua reinterpret these techniques in contemporary installations.

评价

目前还没有评价