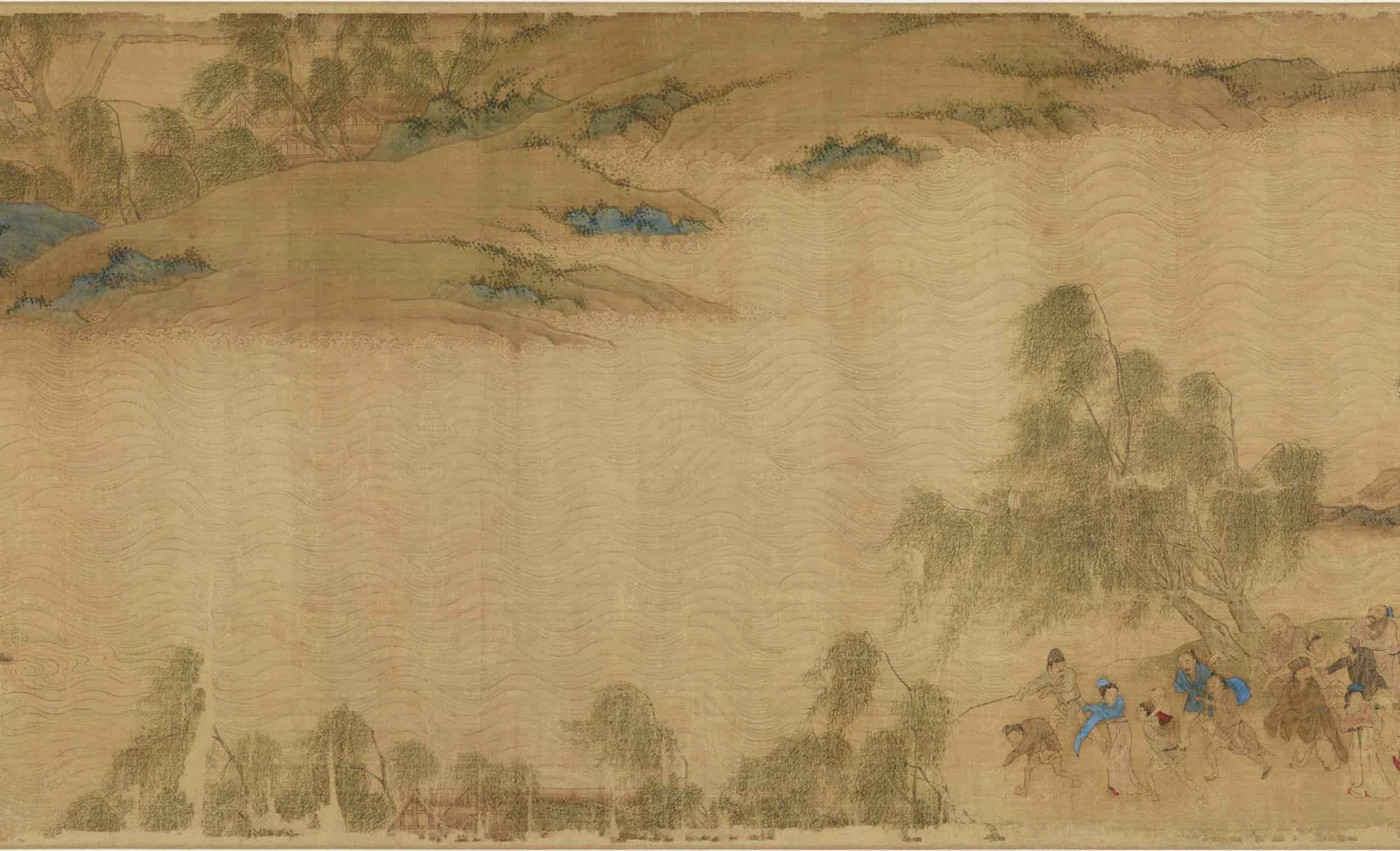

This anonymous Ming Dynasty handscroll, housed at the Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo, depicts the Ming military’s resistance against Japanese pirates (wokou) along China’s eastern coast. Painted in ink and color on paper, the scroll (approx. 30 cm × 10 meters) comprises eight sequential scenes capturing the invasion, plunder, and eventual defeat of the pirates. Key sections include:

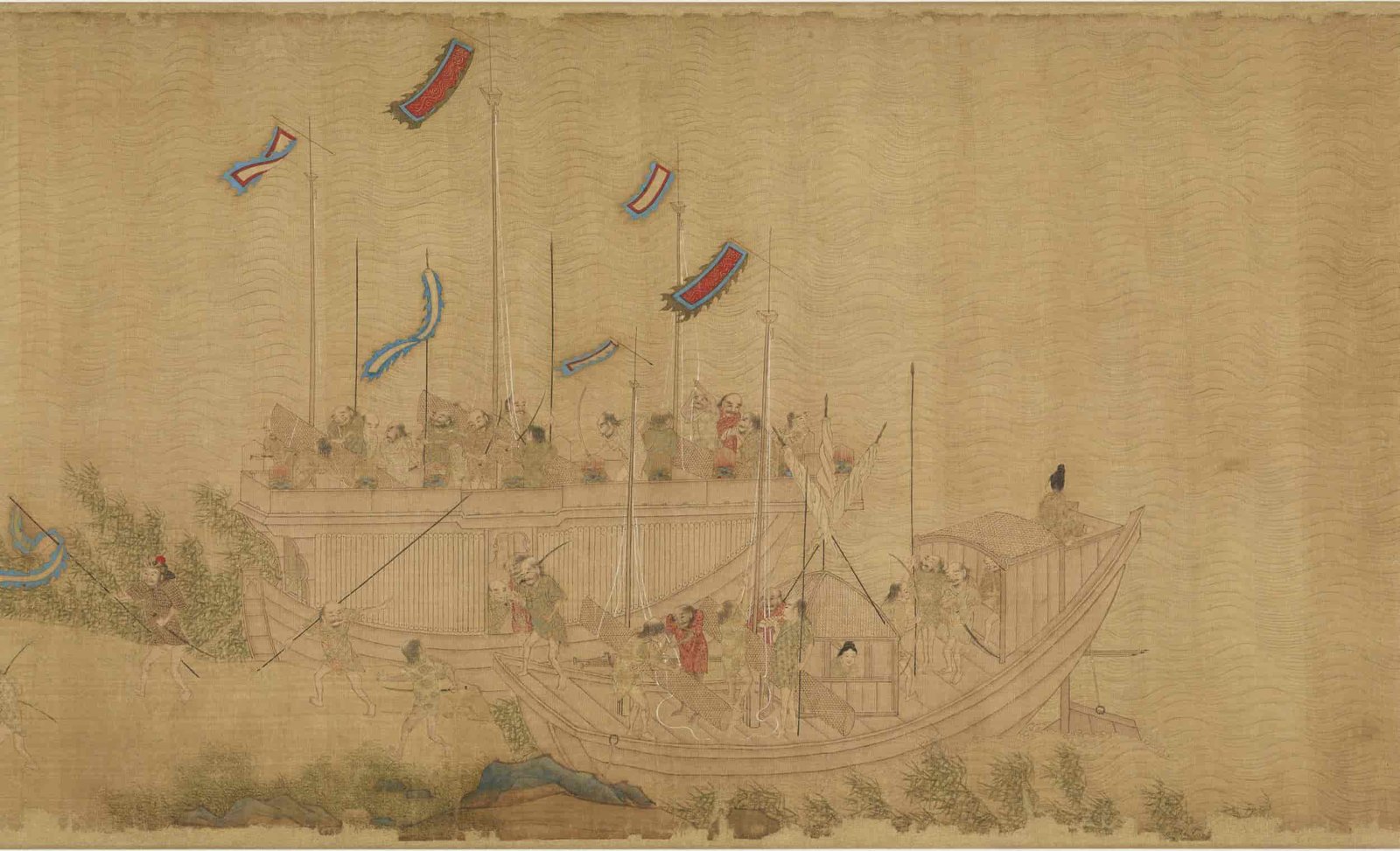

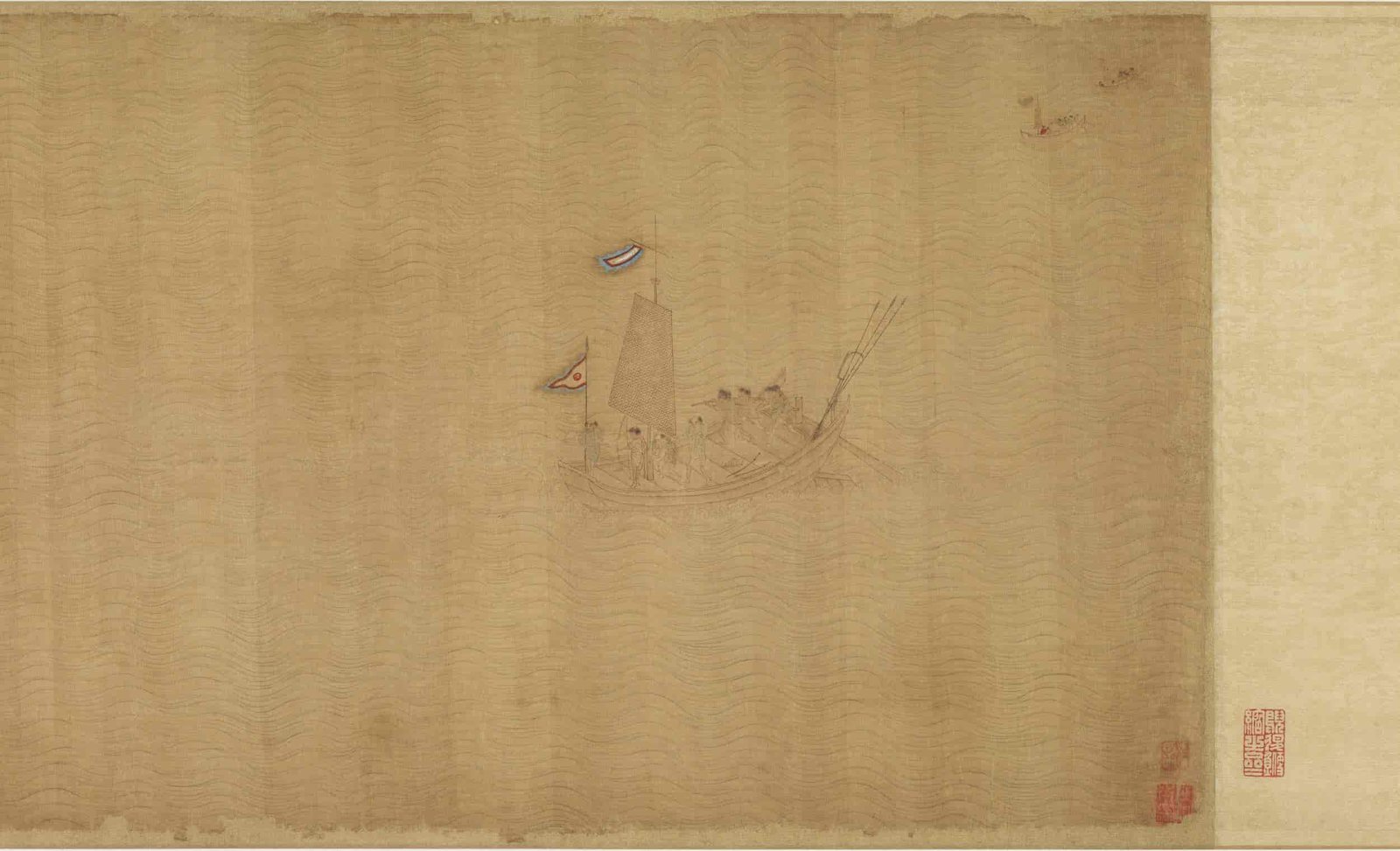

- Japanese Pirate Fleet Arrival : Three flat-bottomed ships with bamboo-mat sails and mixed weaponry (bows, spears, nodachi swords) approach the shore. Notably, the ships blend Chinese and Japanese naval designs, reflecting historical accounts of pirate-modified vessels.

- Pirates Landing and Reconnaissance : Pirates scale walls using ladders, while a lookout perches on a comrade’s shoulders to survey the terrain. A red-clad pirate wields a matchlock gun (teppo), highlighting limited firearm use among raiders.

- Looting and Arson : Villagers flee as pirates pillage homes, carrying bundles and boxes. A commander with dual swords directs the chaos, while another wields a nodachi (oversized sword) matching historical descriptions of Japanese weaponry.

- Naval Battle : Ming forces engage pirates in river combat. Pirates drown under arrow fire, while Ming soldiers attack with spears and hooked poles. A wounded pirate, arrow through his cheek, symbolizes the battle’s ferocity.

- Ming Counteroffensive : Troops march from the fortified “Hai Fang Xin Bao” (海防新堡, New Coastal Defense Fort), led by a mounted commander. Soldiers carry shields, halberds, and zhanmadao (horse-slaying swords), reflecting Ming infantry tactics.

Historical Context:

- Infrared imaging revealed hidden inscriptions like “Hongzhi 4th Year” (弘治四年, 1558) and “Great Ming Divine Victory Coastal Defense Forces” , suggesting the scroll commemorates the 1558 Battle of Yongjia in Zhejiang, where Ming forces repelled pirate raids .

- The term wokou (倭寇) initially referred to Japanese raiders but later included Chinese collaborators. Ming records note “30% true Japanese, 70% local accomplices” .

Artistic Significance:

- Unlike the National Museum of China’s Anti-Wokou Scroll (《抗倭图卷》), this version emphasizes documentary realism—detailed weaponry, pirate attire (half-shaved heads, unlined robes), and ship construction.

- Misattributed to Qiu Ying (仇英, 1494–1552) due to a later label (Taiwan Victory Celebration), its late-Ming style and thematic focus confirm it as an independent work .

Scholarly Debates:

- Scholar Suda Makiko traced the scroll’s 1923 debut in Japan and linked “Hai Fang Xin Bao” to the Yongchang Fort in Wenzhou, built post-1558 raids .

- The mix of Chinese and Japanese ship elements reflects pirates’ hybrid naval adaptations, as described in Chouhai Tubian (《筹海图编》) .

Legacy:

A vital artifact for studying Sino-Japanese maritime conflict, the scroll combines historical narrative with forensic detail, offering insights into Ming coastal defense and cross-cultural piracy.

评价

目前还没有评价