Scroll of the Unicorn’s Hoof(麟趾图卷)

Attributed to Zhou Fang (周昉, 730–800), Tang Dynasty

Held by the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Overview

This Ming-era handscroll (likely 16th century) depicts palace concubines and princes engaged in leisurely activities—chasing butterflies, picking lotus flowers, and bathing infants—capturing a rare, intimate glimpse of imperial domestic life. While traditionally attributed to Tang master Zhou Fang, stylistic analysis reveals it as a “Suzhou fake” (苏州片), blending Tang-inspired figures with Ming artistic conventions. The work exemplifies how Ming artisans recycled classical motifs for collectors, merging Zhou Fang’s iconic “plump beauty” style (周家样) with elements from Qiu Ying’s Spring Morning in Han Palace (汉宫春晓).

Key Scenes & Artistic Hybridity

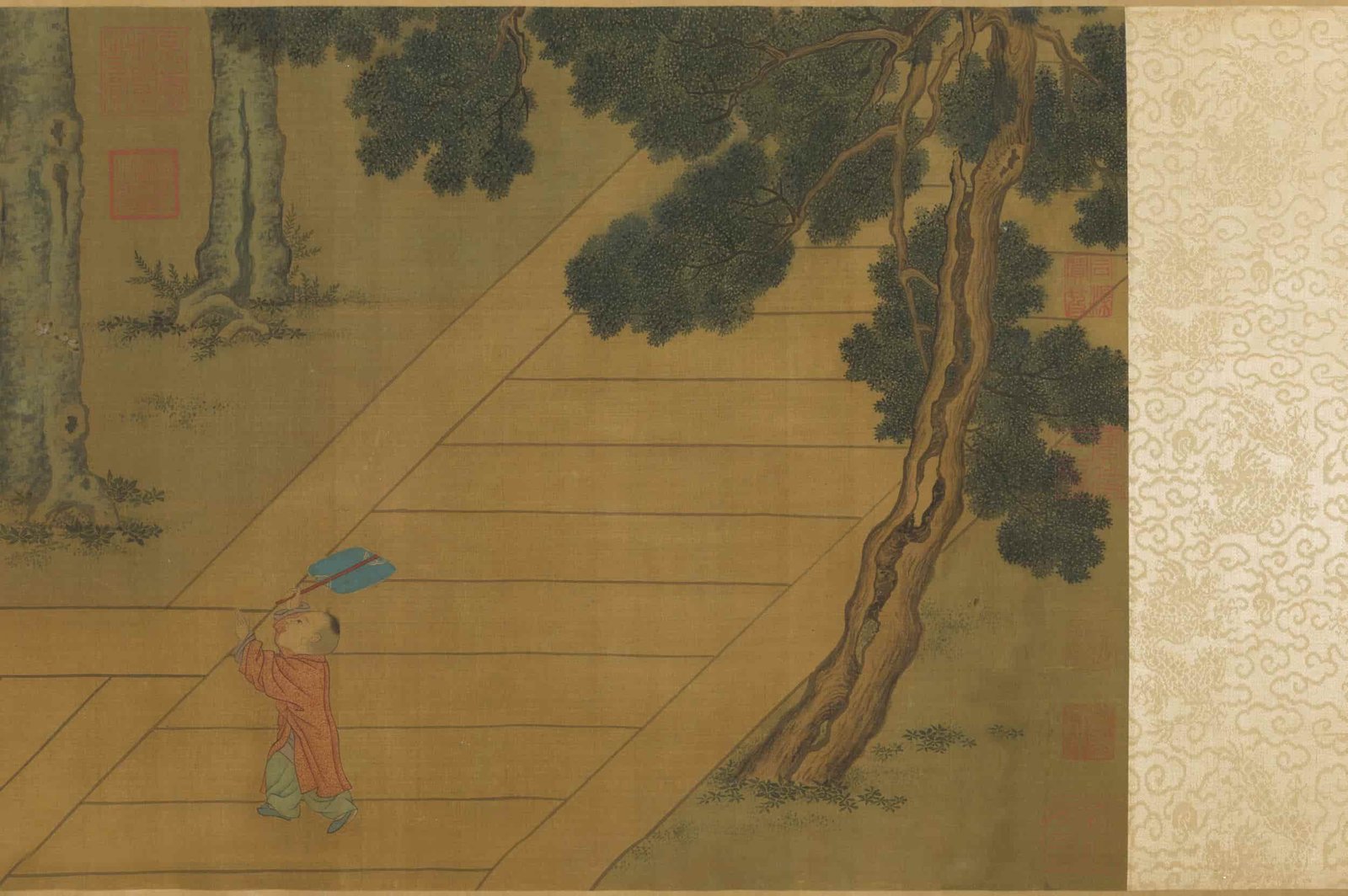

- Royal Children at Play

- Boys in Tang-style high-waisted robes (唐装) chase butterflies, their rounded faces echoing Zhou Fang’s “plump beauty” aesthetic.

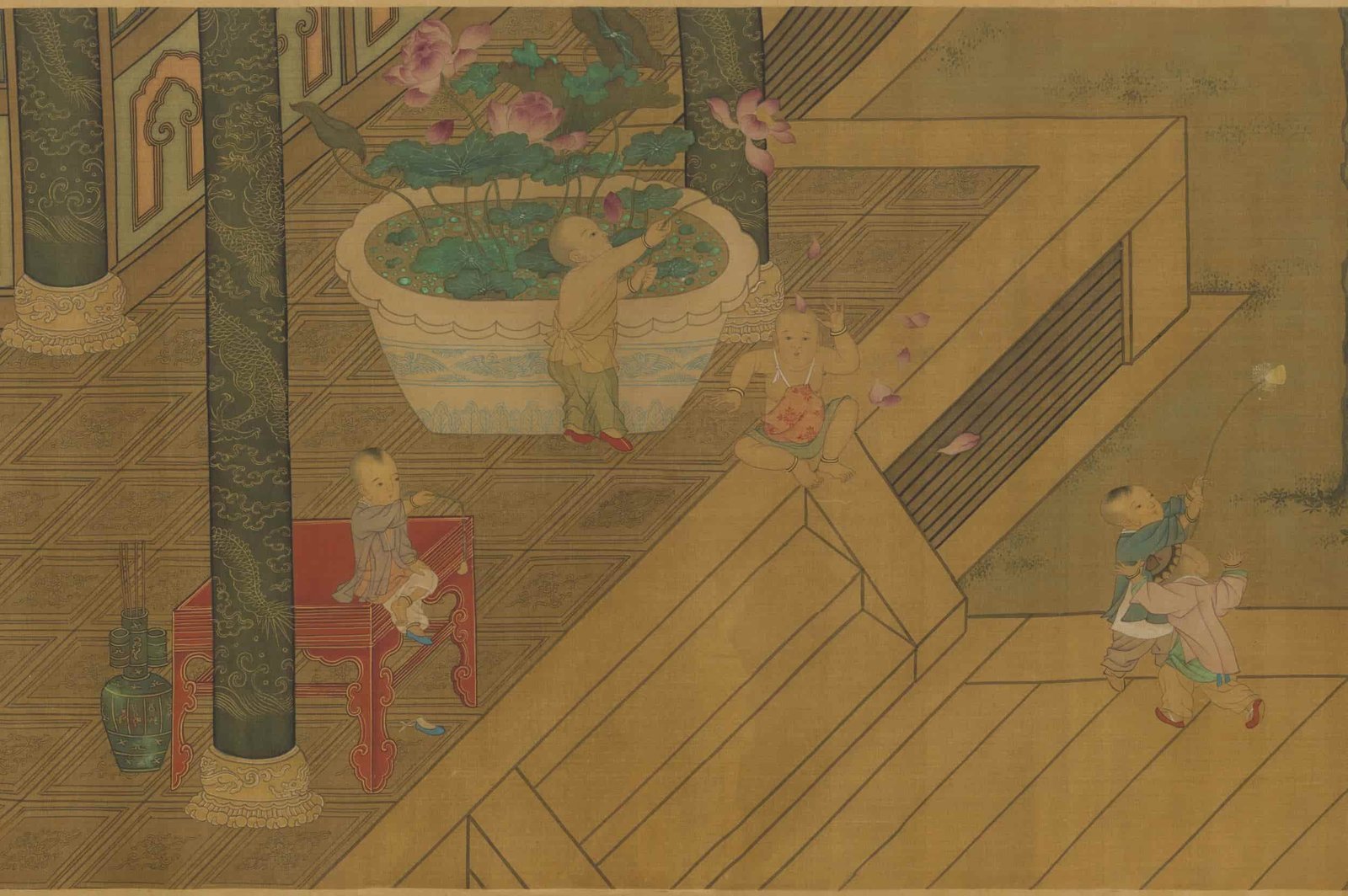

- Infants bathed by attendants mirror child-rearing scenes from other Zhou Fang-attributed works.

- Ming Anachronisms

- A concubine seated in a lacquered chair directly quotes Qiu Ying’s Ming-period compositions.

- Landscape elements show “Suzhou School” mannerisms: delicate brushwork and vibrant mineral pigments.

- Symbolism of “Unicorn’s Hoof”

- The title references Classic of Poetry (《诗经》), where the unicorn (麟) symbolizes noble descendants who uphold virtue—here, implying the princes’ auspicious futures.

Historical Context: The “Suzhou Fake” Phenomenon

- 16th-Century Art Market: Suzhou’s workshops mass-produced “antique” paintings, mixing genuine Tang-Song styles with contemporary Ming tastes.

- Qiu Ying’s Influence: This scroll borrows figures from Qiu’s works, confirming its Ming origin despite Tang attribution.

- Collector Culture: Elite patrons prized such hybrids as displays of cultural literacy, fueling demand for pseudo-classical works.

Colophons & Provenance

- Yu Ji’s Colophon (1345 CE)

- Claims the scroll was a Song Huizong imperial collection item (implausible given Ming style).

- Praises Zhou Fang’s “exquisite skill” in portraying plump figures—a trope used to authenticate Suzhou fakes.

- Zhang Yu’s Colophon (1349 CE)

- Declares most Zhou Fang works are forgeries, but this “divinely preserved” scroll exceptional.

- Ironically, this endorsement likely helped the Ming-era forgery gain credibility.

- Fake Signature: “Zhou Fang” inscribed on a tree trunk mimics Tang calligraphic styles.

Artist Background

Zhou Fang (周昉)

- Tang Dynasty court painter known for “water-moon Guanyin” imagery and voluptuous aristocratic women.

- His “Zhou Family Style” (周家样) influenced East Asian figure painting for centuries.

- Ming forgers exploited his fame by creating “lost works” like this scroll.

Why This Matters

- Cultural Recycling: Demonstrates how Ming artists repackaged Tang aesthetics for new audiences.

- Market Dynamics: Exposes 16th-century China’s sophisticated art forgery networks.

- Stylistic Legacy: The “plump beauty” ideal persisted through Qing dynasty court paintings.

Digital Access: High-resolution scan available via Taipei’s National Palace Museum.

Note for Western Audiences:

- “Unicorn” (麟) here refers to the qilin, a Chinese hybrid creature symbolizing benevolence.

- “Suzhou fakes” weren’t seen as unethical in Ming times but as homages to classical masters.

- Compare to European “after Rubens” workshop practices in the 17th century.

评价

目前还没有评价